THE SUPERIOR COURT OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY

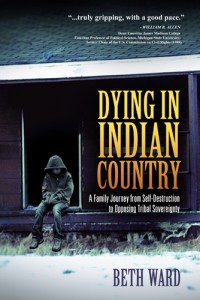

In re Bridget R., et al., Minors, (1996) 41 Cal.App.4th 1483 (Bridget R.).

James R. and Colette R. v. Cindy R.et al.,

January 19, 1996 ,

LLR No. 9601041.CA, Cite as: LLR 1996.CA.41 – “The Pomo Twins”

Contains: Constitutional Limitations upon the Scope of ICWA; Existing Family Doctrine

[1] Filed 1/18/96 Parent and Child, [2]CERTIFIED FOR PUBLICATION

[3] IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

[4] SECOND APPELLATE DISTRICT, [5] DIVISION THREE

[6] In re BRIDGET R., et al., Minors. [7] JAMES R. AND COLETTE R. et al., [8] Petitioners and Appellants, v. [9] CINDY R. et al.,[10] Objectors and Respondents.

[11] DRY CREEK RANCHERIA, et al..,[12] Intervenors and Respondents.

[13] In re BRIDGET R., et al., MINORS. [14] JAMES R. et al.,[15] Petitioners,v. [16] THE SUPERIOR COURT OF LOS ANGELES COUNTY,[17] Respondent;[18] CINDY R., et al., [19] Real Parties in Interest.

[20] B093520 (Super.Ct.No. BN1980 consol. w/BC114849) [21] B093694 [22] APPEAL from an order of the Superior Court of Los Angeles County.

[23] John Henning, Judge. Reversed and remanded with directions.

Counsel

[24] John L. Dodd and Jane A. Gorman for Petitioners and Appellants, the adoptive parents [identified in the opinion as the “R’s”]; Michael F. Kanne for Petitioner and Appellant Vista Del Mar Child and Family Services.

[25] James E. Cohen for Intervenor and Respondent, for Dry Creek Rancheria.

[26] Mitchell L. Beckloff for Respondent Minors, Janette Freeman Cochran, Robert S. Gerstein, for Biological Parents, Farella, Braun & Martel, Norma G. Formanek, Jennifer Schwartz, Joan Heifetz Hollinger, Mark C. Tilden, Alexander & Karshmer, Barbara Karshmer, Sant’Angelo & Trope, Jack F. Trope, Robert J. Miller, Patricia D. Hinrichs, Dunaway & Cross, Michael P. Bentzen, Cary W. Mergele, Wylie, McBride, Jesinger, Sure & Platten, Christopher E. Platten, Marc Gradstein, Mark D. Fiddler, Todd D. Steenson and Randall B. Hicks as Amici Curiae.

Back to the Top

[27] California recognizes the principle that children are not merely chattels belonging to their parents, but rather have fundamental interests of their own. (In re Jasmon O. (1994) 8 Cal.4th 398, 419.) Such fundamental interests are of constitutional dimension. This principle is central to our resolution of the multiple and complex issues presented by this case.

[28] We reverse an order of the trial court made pursuant to sections 1913 and 1914 of the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978 (25 U.S.C.A. 1901 et seq.; hereafter “ICWA” or “the Act”). The court’s order invalidated a voluntary relinquishment of parental rights respecting Bridget and Lucy R., twin two-year-old girls, and ordered the twins removed from their adoptive family, with whom they have lived since birth, and returned to the extended family of the biological father. The adoptive parents (hereafter the “R’s” or “adoptive parents”) appealed, *fn1 joined by the licensed adoption agency through which the twins were placed. *fn2

[29] The twins are of American Indian descent, and the within dispute over their prospective adoption and custody raises issues concerning the scope of ICWA. Specifically, it raises the question of whether the Act should be limited in its application, as some courts have limited it, to children who not only are of Indian descent, but also belong to an “existing Indian family.” (See, e.g., In re Adoption of Crews (1992) 118 Wash.2d 561 [825 P.2d 305]; Matter of Adoption of Baby Boy L. (1982) 231 Kan. 199 [643 P.2d 168].) We conclude that question must be answered in the affirmative.

[30] ICWA was enacted by Congress to protect the best interests of Indian children and promote the stability of Indian tribes and families. (25 U.S.C.A. Section(s) 1902; Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield (1989) 490 U.S. 30, 32-37 [104 L.Ed. 2d 29, 109 S.Ct. 1597];

[31] Here, the twins’ biological parents, Richard A. (“Richard”) and Cindy R. (“Cindy”), initially relinquished the twins to appellant Vista Del Mar Child and Family Services (“Vista Del Mar”) pursuant to section 8700 of California’s Family Code for adoption by the R’s, a non-Indian couple. However, Richard and Cindy later purported to withdraw their consent. With the assistance of the Dry Creek Rancheria of Pomo Indians, the federally recognized Indian tribe from which Richard is descended (hereafter, the “Tribe”), they initiated proceedings under ICWA to invalidate their relinquishments of parental rights. It is undisputed that the relinquishments were not executed in the manner required by ICWA. It is also undisputed that Richard and the twins are now recognized by the Tribe as tribal members. However, the record raises substantial doubt as to whether Richard, who, at all relevant times, resided several hundred miles from the tribal reservation, ever participated in tribal life or maintained any significant social, cultural or political relationship with the Tribe.

Back to the Top

[32] Although urged by Vista Del Mar and the R’s to apply the “existing Indian family doctrine” in this case, and uphold the relinquishments of parental rights unless the biological parents established that they were such a family, the trial court declined to apply that doctrine or hold any hearing with respect thereto. The court simply declared the relinquishments invalid as violative of ICWA and ordered the twins placed in the custody of their paternal grandparents, who were appointed temporary guardians. The trial court also dismissed a petition by the adoptive parents to terminate the biological parent’s parental rights on the ground of abandonment. (Fam. Code, Section(s) 7822.) The court found ICWA precluded it from proceeding on that petition.

[33] As we explain, recognition of the existing Indian family doctrine is necessary in a case such as this in order to preserve ICWA’s constitutionality. We hold that under the Fifth, Tenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, ICWA does not and cannot apply to invalidate a voluntary termination of parental rights respecting an Indian child who is not domiciled on a reservation, unless the child’s biological parent, or parents, are not only of American Indian descent, but also maintain a significant social, cultural or political relationship with their tribe. Because the factual issues raised by such a rule have not been resolved, we reverse the trial court’s order and remand the case for a determination of whether the twins’ biological parents had such a relationship at the time that they voluntarily acted to relinquish their parental rights under California law. In the event that the trial court, after consideration of all the evidence, determines that such a relationship did not exist, then those relinquishments will be valid and binding and ICWA will not bar any pending adoption proceedings. On the other hand, if the trial court finds that the biological parents did have a significant social, cultural or political relationship with the Tribe, and therefore the provisions of ICWA can properly be applied, then a further guardianship hearing will be required to resolve the question of whether the twins should be removed from the custody of the R’s.

Back to the Top

[34] FACTUAL BACKGROUND *fn3

[35] Bridget and Lucy, twin girls, were born on November 9, 1993, in Los Angeles County, California, to Richard and Cindy. He is of American Indian descent, while she is descended from the Yaqui tribe of Mexico. *fn4 Richard is three-sixteenths Pomo and is currently an enrolled member of the Tribe.

[36] The Tribe, which occupies a reservation in Sonoma County, in northern California, has approximately 225 enrolled members, of whom approximately twenty-five live on the reservation. Since 1973, the Tribe has been governed by a set of Articles of Association, which, among other things, establish the qualifications of tribal membership. Under the Articles, such membership includes all persons who

(1) have completed an application for membership, and

(2) are named in a June 4, 1915 Bureau of Indian Affairs census of Indians “in, near and up Dry Creek from Healdsburg” and Indians “in and near Geyserville,” or are descendants of persons in those censuses, or are both California Indians and spouses of tribal members who hold valid assignments of land on the Rancheria. A person who is otherwise qualified to be a member is disqualified if he or she has been formally enrolled in another tribe, band or group, or has received an allotment of land by virtue of an affiliation with such other tribe, band or group. The Tribe’s Board of Directors is responsible for maintaining a current membership roll.

[37] Before the adoption of the Articles of Association in 1973, the Tribe was governed solely by custom and tradition, under which any lineal descendant of a historic tribal member was automatically a member of the Tribe and was recognized as such from birth. Marcellena Becerra, the tribal administrator, testified in the proceedings below that, when the Articles of Association were adopted, it was determined that existing members would continue to be recognized as members without the need to enroll formally. Thus, although his name is not on the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ enrollment list for the Tribe, Richard, who was born in 1972, is recognized as a tribal member according to pre-1973 customs. He became an enrolled member of the Tribe March of 1994, after the present custody dispute began, when his mother, Karen A. (“Karen”), submitted a membership application on his behalf.

[38] In mid-1993, Richard and Cindy discovered that Cindy was pregnant. Richard was then 21 years old, and Cindy was 20. They then lived together with their two sons, Anthony, age two, and Richard Andrew, age one, in the city of Whittier in Los Angeles County, California. However, by August of 1993, Cindy and the children were living in a shelter. Richard and Cindy realized they would not be able care for the expected twins, and so determined to relinquish them for adoption. They consulted Durand Cook, an attorney specializing in adoption, for this purpose.

[39] Richard initially identified himself to Cook as one quarter American Indian. However, when told the adoptions would be delayed or prevented if Richard’s Indian ancestry were known, Richard filled in a revised form, omitting the information that he was Indian.

Back to the Top

[40] During the ninth month of Cindy’s pregnancy, she and Richard met with a social worker from Vista Del Mar. On November 11 and 12 respectively, after receiving counseling concerning the relinquishment and adoption process as required by regulations promulgated pursuant to Family Code section 8621 (Cal. Code Regs., tit. 22, Section(s) 35128 et seq.), Richard and Cindy signed documents relinquishing the twins to Vista Del Mar, with the intent that they would be adopted by the R’s *fn5 . The relinquishments were filed with the state Department of Social Services on November 23, 1993. *fn6 Although the relinquishment documents contained direct queries as to whether either biological parent was of Indian descent, Richard concealed his Indian ancestry and listed his “basic ethnic group” as “white.” A few days after the relinquishments were executed, the R’s returned with the twins to their home in Ohio, where they have lived as a family ever since. On May 4, 1994, the R’s filed a petition in Franklin County, Ohio to adopt Bridget and Lucy. That petition is presumably still pending. *fn7

[41] In December of 1993, Richard told his mother, Karen, about Cindy’s pregnancy, the birth of the twins and their adoption. In early February of 1994, Karen contacted attorney Cook. At approximately the same time, Karen contacted the Tribe. A representative of the Tribe contacted Cook in February or March of 1994. Cook informed the R’s of this communication. On March 4, 1994, Amy Martin, the Tribe’s Chairperson, wrote to the Los Angeles County Children’s Court, stating that the twins were potential members of the Tribe and requesting intervention in any proceedings concerning them. On approximately that same date, Karen submitted tribal enrollment applications for herself, Rchard, the twins, and Richard’s two other children. On March 9, 1994, Amy Martin wriote to Vista Del Mar, stating that the twins were of Indian descent, and Karen, their paternal grandmother, wished them placed within the extended Indian family.

[42] During these weeks and months, the relationship between Richard and Cindy was deteriorating. On April 27, 1994, Cindy obtained a restraining order, which required Richard to remain at least 100 yards from Cindy and their two sons, Anthony and Richard Andrew. In a declaration in support of her application for the restraining order, Cindy related that on numerous occasions during March, Richard hit and kicked Cindy and pushed her down, broke furniture, and abused the one-and two-year-old children by picking them up by the neck and shaking or dropping them, poking them in the face, or hitting them in the head. On at least one of these occasions, Richard was intoxicated. *fn8

[43] On April 22, 1994, Richard sent to Vista Del Mar a letter which stated that Richard wished to rescind his relinquishment of the twins and to have them raised within his extended family. This letter was drafted by Lorraine Laiwa, a member of the Tribe. Laiwa read the letter to Richard over the telephone. After he approved its contents, she mailed it to him for his signature. After signing the letter, Richard sent the original to Vista Del Mar and a copy to his mother. Richard later testified that his intent, when he signed the letter, was to place the twins with his sister.

[44] On June 20, 1994, Richard had a meeting with Elias Lefferman, Ph.D., Director of Community Services at Vista Del Mar, concerning the request to rescind his relinquishment of the twins. During this meeting, Richard acknowledged that he had previously concealed his Indian ancestry. He stated that his decision to rescind his relinquishment of parental rights was prompted by his mother, Karen, so that Richard’s sister could raise the twins. Vista Del Mar denied Richard’s request to withdraw the relinquishments, and the proceedings that are now before us for review followed. *fn9

Back to the Top

[45] CONTENTIONS

[46] On appeal and in their petition for writ of mandate, the adoptive parents contend that:

(1) the trial court erred in failing to recognize the “existing Indian family” doctrine and

(2) ICWA is unconstitutional, unless limited by the “existing Indian family” doctrine, in that it

(a) impedes the exercise of fundamental rights of adopted children and their adoptive families;

(b) creates an impermissible racial classification, and

(c) exceeds the enumerated powers of Congress and violates the Tenth Amendment.

[47] In the alternative, the adoptive parents argue that, even if ICWA is constitutional and is not limited by the “existing Indian family” doctrine, the trial court’s order must be reversed, because:

(1) Richard is not a presumed father,

(2) the Tribe is precluded from retroactively enrolling Richard and the twins as tribal members,

(3) the twins are only 3/32 Indian,

(4) the biological parents, having concealed Richard’s Indian heritage in order to facilitate the adoption, are estopped from invoking ICWA to prevent it and

(5) ICWA’s provisions do not defeat the requirement that a hearing must be held on the issue of whether a change of custody to the extended biological family is in the best interests of the children or will be a detriment to them.

Back to the Top

[48] DISCUSSION

[49] 1. Summary of Relevant Portions of ICWA.

[50] ICWA, enacted by Congress to prevent the further “wholesale separation of Indian children from their families” through state court proceedings, was prompted by studies conducted in the 1970’s which showed that Native American children were being removed from their homes, through both foster care and adoption, in disproportionate numbers. (Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield, supra, 490 U.S. at pp. 32-37.)

[51] The Act is broken down into two titles. In this case, we are concerned only with Title I (25 U.S.C. Section(s) 1901 – 1923) which provides for the allocation of jurisdiction over Indian child custody proceedings between Indian tribes and the States and establishes federal standards to protect Indian families. Title II of the Act (25 U.S.C. Section(s) 1931 – 1963) provides for grants to Indian tribes and organizations to operate child and family service programs.

[52] Sections 1901 and 1902 set forth the historical and policy bases of ICWA. The stated policies are to protect the best interests of Indian Children and protect the cultural heritage of Indian nations from destruction through the removal of children from Indian tribes. Section 1903 defines the Act’s operative terms.

An “Indian child” is defined as “any unmarried person who is under age eighteen and either

(a) is a member of an Indian tribe or

(b) is eligible for membership in an Indian tribe and is the biological child of a tribal member.” (25 U.S.C. Section(s) 1903, subd. (4).)

An “Indian tribe“ is “any Indian tribe, band, nation, or other organized group or community of Indians recognized as eligible for the services provided to Indians by the Secretary because of their status as Indians. . . .” (25 U.S.C.A. 1903, subd. (8).)

Back to the Top

[53] Section 1911,

subdivision (a), gives an Indian tribe “exclusive jurisdiction as to any State over any child custody proceeding involving an Indian child who resides on or is domiciled within” the tribal reservation. When an Indian child who is not domiciled on a reservation is the subject of child custody proceedings in a state court, section 1911,

subdivision (b), provides that, absent good cause, jurisdiction shall be transferred to the child’s tribe upon request by either parent or the tribe.

Subdivision (c) provides that an Indian child’s tribe may intervene in any state court custody proceeding affecting the child. Subdivision (d) requires all jurisdictions within the United States to give full faith and credit to the acts of an Indian tribe that are applicable to Indian child custody proceedings.

[54] Section 1912 provides standards for involuntary proceedings respecting the removal of Indian children from their homes. These include a requirement of clear and convincing evidence of a threat of serious harm before an Indian child may be placed in foster care or in the custody of a guardian (Section(s) 1912, subd. (e)), and a requirement of proof beyond a reasonable doubt, supported by the testimony of qualified experts, of a threat of serious harm before parental rights respecting an Indian child may be terminated (Section(s) 1913, subd. (f)).

[55] Section 1913 sets forth standards for voluntary foster care placements and voluntary terminations of parental rights.

Subsection (a) provides that Indian parents who relinquish their parental rights must execute the relinquishments in writing before a judge, who must certify that the proceedings were explained to the parents in a language they understand. Subsection (a) further provides that “Any consent given prior to, or within ten days after, birth of the Indian child shall not be valid.”

Subsection (b) provides that a parent or Indian custodian may withdraw consent to a foster care placement at any time, and upon such withdrawal, the child must be returned.

ubsection (c) provides that a parent or Indian custodian may withdraw consent to termination of parental rights at any time until entry of a final order of adoption or termination, and upon such withdrawal, the child must be returned.

Subsection (d) provides that a final court decree of adoption may be overturned at any time within two years of its entry if parental consent was obtained through fraud or duress.

[56] Section 1914 of ICWA allows any Indian child, parent or Indian custodian from whom a child was removed, and the Indian child’s tribe to petition a court of competent jurisdiction to invalidate a foster care placement or termination of parental rights upon a showing that such action violated any provision of sections 1911, 1912 or 1913.

Back to the Top

[57] 2. The “Existing Indian Family” Doctrine

[58] As noted above, ICWA applies to any child who is either: (1) a member of an Indian tribe, or (2) eligible to be a member, and the biological child of a member of a tribe. (Section(s) 1903, subd. (4).) However, some courts have declined to apply the Act where a child is not being removed from an existing Indian family, because, in such circumstances, ICWA’s underlying policies of preserving Indian culture and promoting the stability and security of Indian tribes and families are not furthered. (In re Adoption of Crews, supra, 825 P.2d 305; Matter of Adoption of Baby Boy L., supra, 643 P.2d 168.)

[59] The earliest case to articulate what later became known as the existing Indian family doctrine was Matter of Adoption of Baby Boy L., supra, 643 P.2d 168. In that case, the Kansas Supreme Court observed that the purpose of ICWA was to maintain family and tribal relationships existing in Indian homes and to set standards for removal of Indian children from an existing Indian environment. (643 P.2d at p. 175.) The court found that the child whose custody was at issue in that case had been relinquished by his non-Indian mother at birth and had never been in the custody of his Indian father. The child thus had never been part of an Indian family relationship. Preservation of an Indian family was therefore not involved in the case; consequently, ICWA did not apply. (643 P.2d at p. 175; see also Matter of Adoption of T.R.M. (Ind., 1988) 525 N.E.2d 298, 303; Claymore v. Serr (S.D., 1987) 405 N.W.2d 650, 654; In the Interest of S.A.M. (Mo., 1986) 703 S.W.2d 603, 609; Adoption of Baby Boy D. (Ok., 1985) 742 P.2d 1059, 1064, cert. den. by Harjo v. Duello (1988) 484 U.S. 1072 [98 L.Ed.2d 1005, 108 S.Ct. 1042].)

[60] While the above cases found ICWA inapplicable because the Indian child himself (or herself) had never lived in an Indian environment, other cases have focused upon the question of whether the child’s natural family was part of an Indian tribe or community or maintained a significant relationship with one. In Matter of Adoption of Crews, supra, 825 P.2d 305, a case involving facts very similar to those before us, the Supreme Court of Washington found ICWA inapplicable to an adoption proceeding where the biological parents had no substantial ties to a specific tribe, and neither the parents nor their families had resided or planned to reside within a tribal reservation, although the birth mother was formally enrolled as a tribal member. In such a situation, the court found the application of ICWA would not further the Act’s policies and purposes and would consequently not be proper. (825 P.2d at pp. 308-310; see also, Hampton v. J.A.L. (La.App., 2 Cir., 1995) 658 So.2d 331, 336, aff’d. by Supreme Court of Louisiana at 662 So.2d 478.)

[61] In California, at least two courts have recognized the existing family doctrine. In In re Wanomi P. (1989) 216 Cal.App.3d 156, the court found ICWA inapplicable by its express terms, because the tribe to which the child’s mother belonged was a Canadian tribe, not a federally recognized tribe, as required by section 1903, subdivision (8) of ICWA. (216 Cal.App.3d at p. 166.) However, the court also observed, in dictum, that regulating the unwarranted removal of children from Indian families by nontribal agencies was among the objectives of ICWA, and no evidence suggested the existence of an Indian family from which the minor was being removed. (Id. at p. 168.) Thus, the court noted that there would be no occasion for an application of ICWA. (Ibid.) In In re Baby Girl A. (1991) 230 Cal.App.3d 1611, the majority found the baby’s tribe had a right to intervene in adoption proceedings. However, the right of intervention existed under state law, independently of ICWA. (230 Cal.App.3d at pp. 1618-1619.) The court found that, upon remand of the action, the preferences for the placement of Indian children in Indian families or settings, which are provided in section 1915 of ICWA, need not be followed if the trial court found the child had no actual Indian family ties. (230 Cal.App.3d at pp. 1620-1621.)

Back to the Top

[62] Two other California courts, however, have refused to apply the existing Indian family doctrine, or at least that version of the doctrine which holds that ICWA applies only if the child himself (or herself) has lived in an Indian family or community. In Adoption of Lindsay C., supra, 229 Cal.App.3d 404, the court characterized the doctrine as follows: “Generally speaking, [the doctrine] hold[s] the Act inapplicable in adoption proceedings involving an illegitimate Indian child who has never been a member of an Indian home or Indian culture, and who is being given up by his or her non-Indian mother.” (229 Cal.App.3d at p. 410.) The Lindsay C. court rejected the doctrine as so characterized. (Id. at pp. 415-416.) The trial court had found the tribe of the child’s unwed father had no right to notice of a pending step-parent adoption affecting the child, because he was the illegitimate child of a non-Indian mother, had always resided with the non-Indian mother, and had never been in the care or custody of the natural father, nor had any connection with Indian culture. Thus, without ever considering whether the natural father had significant ties with an Indian community, which he might one day share with the child if their family ties were not severed, the trial court concluded that no issue of the preservation of an Indian family was involved, as the child had never been a part of an Indian family. (Id. at p. 415.) The Court of Appeal rejected this reasoning and reversed. (Id. at pp. 415-416.)

[63] Likewise in In re Junious M. (1983) 144 Cal.App.3d 786, in a proceeding under (former) Civil Code section 232, the child’s mother informed the court on the third day of trial that she was of Indian descent. (144 Cal.App.3d at pp. 788-789.) The court found the mother’s tribe had a right to notice of the proceedings and a right to intervene, even though the minor had never lived in an Indian environment. “The language of the Act contains no [existing Indian family] exception to its applicability, and we do not deem it appropriate to create one judicially.” (Id at p. 796, citing A.B.M. v. M.H. (Alaska 1982) [64] 651 P.2d 1170, 1173.)” *fn10

[64] 651 P.2d 1170, 1173.)” *fn10

[65] We agree that a rule which would preclude the application of ICWA to any Indian child who has not himself (or herself) lived in an Indian family does not comport with either the language or purpose of the Act. Moreover, the United States Supreme Court has implicitly rejected any such limitation on ICWA. In Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield, supra, 490 U.S. 30, the only case in which the federal high court has construed ICWA, application of the Act’s tribal jurisdiction provisions (25 U.S.C.A. Section(s) 1911, subd. (a)) was challenged by the adoptive parents of illegitimate twin babies whose parents were enrolled members of an Indian tribe and were residents of the tribal reservation. (490 U.S. at pp. 37-38.) The babies were born off of the reservation and immediately relinquished to a non-Indian family, who adopted them in the state Chancery court. The birth mother returned home to the reservation after giving birth. On a subsequent motion by the tribe to vacate the adoption on the ground that the tribal court had exclusive jurisdiction over matters affecting the children’s custody, the state court found the children had never resided, or even been physically present, on the reservation, and were thus not domiciled there. Consequently, the court found ICWA did not apply. (Ibid.) The Supreme Court reversed (Id. at p. 41), finding that

(1) a general federal rule of domicile must apply for purposes of determining jurisdiction under ICWA (Id. at pp. 43-45);

(2) under such rule, the children’s domicile at birth followed that of their natural mother, and she was domiciled on the reservation (Id. at pp. 47-49);

(3) therefore, the tribe had exclusive jurisdiction over custody proceedings affecting the children under section 1911, subdivision (a). (Id. at p. 53.)

Back to the Top

[66] Holyfield establishes, by clear implication, that an application of ICWA will not be defeated by the mere fact that an Indian child has not himself (or herself) been part of an Indian family or community. However, it does not follow from Holyfield that ICWA should apply when neither the child nor either natural parent has ever resided or been domiciled on a reservation or maintained any significant social, cultural or political relationship with an Indian tribe. *fn11 To the contrary, in our view, there are significant constitutional impediments to applying ICWA, rather than state law, in proceedings affecting the family relationships of persons who are not residents or domiciliaries of an Indian reservation, are not socially or culturally connected with an Indian community, and, in all respects except genetic heritage, are indistinguishable from other residents of the state. These impediments arise from the due process and equal protection guarantees of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments and from the Tenth Amendment’s reservation to the states of all powers not delegated to the federal government. We must, of course, construe the statute to uphold its constitutionality. (Edward J. DeBartolo Corp. v. Florida Gulf Coast Bldg. & Const. Trades Council (1983) 485 U.S. 568, 575 [99 L.Ed.2d 645, 108 S.Ct. 1392]; Adoption of Kelsey S. (1992) 1 Cal.4th 816, 826.)

[67] 3.

Constitutional Limitations Upon the Scope of ICWA

[68] a. Due Process

The intent of Congress in enacting ICWA was to “protect the best interests of Indian children,” as well as “promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families.” (25 U.S.C. Section(s) 1902.) These two elements of ICWA’s underlying policy are in harmony in the circumstance in which ICWA was primarily intended to apply — where nontribal public and private agencies act to remove Indian children from their homes and place them in non-Indian homes or institutions. (See 25 U.S.C. Section(s) 1901, subd. (4).) But in cases such as this one, where, owing to noncompliance with ICWA’s procedural requirements, ICWA’s remedial provisions are invoked to remove children from adoptive families to whom the children were voluntarily given by the biological parents, the harmony is bound to be strained. Indeed, in circumstances of this kind, the interests of the tribe and the biological family may be in direct conflict with the children’s strong needs, which we find to be constitutionally protected, to remain through their developing years in one stable and loving home.

[69] An individual’s many related interests in matters of family life are compelling and are ranked among the most basic of civil rights. (Quilloin v. Walcott (1978) 434 U.S. 246, 255 [54 L.Ed.2d 511, 98 S.Ct. 549]; In re Marilyn H. (1993) 5 Cal.4th 295, 306.) The United States Supreme Court has stated that “[t]he intangible fibers that connect parent and child have an infinite variety. They are woven throughout the fabric of our society, providing it with strength, beauty and flexibility. It is self-evident that they are sufficiently vital to merit constitutional protection in appropriate cases.” (Lehr v. Robertson (1983) 463 U.S. 248, 256 [77 L.Ed.2d 614, 103 S.Ct. 985].) The high court has explained that its decisions which accord federal constitutional protection to certain parental rights rest upon “the historic respect — indeed, sanctity would not be too strong a term — traditionally accorded to the relationships that develop within the unitary family.” (Michael H. v. Gerald D. (1989) 491 U.S. 110, 123 [105 L.Ed.2d 91, 109 S.Ct. 2333].)

[70] Family rights are afforded not only procedural but also substantive protection under the due process clause. (Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390, 399-401 [67 L.Ed.1042, 43 S.Ct. 625] [law against teaching foreign languages in elementary schools did not serve sufficiently compelling public purpose to justify infringement of due process rights of students to acquire knowledge and of parents to control their children’s education]; Stanley v. Illinois (1972) 405 U.S. 645, 649 [31 L.Ed.2d 561, 92 S.Ct. 1208] [“[A]s a matter of due process of law, Stanley was entitled to a hearing on his fitness as a parent before his children were taken from him. . . .”]; Santosky v. Kramer (1982) 455 U.S. 745, 753 [71 L.Ed.2d 599, 102 S.Ct. 1388] [“When the State moves to destroy weakened familial bonds, it must provide the parents with fundamentally fair procedures.”]; Moore v. East Cleveland (1977) 431 U.S. 494, 502 [52 L.Ed.2d 531, 97 S.Ct. 1932] [local ordinance which limited occupancy of a dwelling unit to members of a nuclear family violated Due Process Clause].) Substantive due process prohibits governmental interference with a person’s fundamental right to life, liberty or property by unreasonable or arbitrary legislation. (Moore v. East Cleveland, supra, 431 U.S. at pp. 501-502; In re David B. (1979) 91 Cal.App.3d 184, 192-193.) Legislation which interferes with the enjoyment of a fundamental right is unreasonable under the Due Process Clause and must be set aside or limited unless such legislation serves a compelling public purpose and is necessary to the accomplishment of that purpose. In other words, such legislation would be subject to a strict scrutiny standard of review. (Moore v. East Cleveland, supra, 431 U.S. at p. 499; Bates v. City of Little Rock (1960) 361 U.S. 516, 524 [4 L.Ed.2d 480, 80 S.Ct. 412]; Sherbert v. Verner (1963) 374 U.S. 398, 406 [10 L.Ed.2d 965, 83 S.Ct. 1790]; see also Poe v. Ullman (1961) 367 U.S. 497, 547 [6 L.Ed.2d 989, 81 S.Ct. 1752], dis. opn of Harlan, J.)

[71] When discussing constitutional protections of family relationships, the courts have focused more often upon the rights of parents than those of children. The United States Supreme Court has declared that the interests “of a man in the children he has sired and raised . . .undeniably warrants deference” (Stanley v. Illinois, supra, 405 U.S. at p. 651; italics added) and that parents’ interest in the “care, companionship, custody and management” of their children has “`a momentum for respect lacking when appeal is made to liberties which derive merely from shifting economic arrangements.’ [Citation.]” (Ibid., italics added; see also Santosky v. Kramer, supra, 455 U.S. at p. 753; Lassiter v. Department of Social Services (1981) 452 U.S. 18, 27 [68 L.Ed.2d 640, 101 S.Ct. 2153].) The California Supreme Court has likewise declared a parent’s interest in the care, custody and management of his or her children to be “a compelling one, ranked among the most basic of civil rights.” (In re Marilyn H., supra, 5 Cal.4th at p. 306; see also Adoption of Kelsey S., supra, 1 Cal.4th at pp. 830-848; In re Angelia P. (1981) 28 Cal.3d 908, 916.)

[72] However, the courts have described the constitutional principles which govern familial rights in language which strongly suggests the Constitution protects the familial interests of children just as it protects those of parents. The federal high Court has said that “the relationship between parent and child is constitutionally protected” (Quilloin v. Walcott, supra, 434 U.S. at p. 255; italics added) and also has “emphasized the paramount interest in the welfare of children and has noted that the rights of the parents are a counterpart of the responsibilities they have assumed.” (Lehr v. Robertson, supra, 463 U.S. at p. 257.) Our own Supreme Court has stated that the right of parents to the care, custody and management of their children, although fundamental, is not absolute, and has stated that “[c]hildren, too, have fundamental rights — including the fundamental right to be protected from neglect and to `have a placement that is stable [and] permanent.’ ” (In re Jasmon O., supra, 8 Cal.4th 398, 419, quoting In re Marilyn H., supra, 5 Cal.4th at p. 306.) “Children are not simply chattels belonging to the parent, but have fundamental interests of their own that may diverge from the interests of the parent.” (In re Jasmon O., supra, 8 Cal.4th at p. 419; italics added.)

Back to the Top

[73] Moreover, as a matter of simple common sense, the rights of children in their family relationships are at least as fundamental and compelling as those of their parents. If anything, children’s familial rights are more compelling than adults’, because children’s interests in family relationships comprise more than the emotional and social interests which adults have in family life; children’s interests also include the elementary and wholly practical needs of the small and helpless to be protected from harm and to have stable and permanent homes in which each child’s mind and character can grow, unhampered by uncertainty and fear of what the next day or week or court appearance may bring. (See generally, In re Jasmon O., supra, 8 Cal.4th at p. 419.)

[74] Cases which hold that deference is to be accorded to parental rights do so in part on the assumption that children’s needs generally are best met by helping parents achieve their interests. (Santosky v. Kramer, supra, 455 U.S. at pp. 759-761; Stanley v. Illinois, supra, 405 U.S. at p. 649; Cynthia D. v. Superior Court (1993) 5 Cal.4th 242,. 253-254; In re Angelia P., supra, 28 Cal.3d at pp. 916-917.) In some situations, however, children’s and parents’ rights conflict, and in these situations, the legal system traditionally protects the child. (Cynthia D. v. Superior Court,, supra, 5 Cal.4th at p. 254; In re Angelia P., supra, 28 Cal.3d at p. 917.)

75] Circumstances in which a parent’s and child’s interest diverge, and the child’s interests are found more compelling, include circumstances where a child has been in out-of-home placement under the jurisdiction of a dependency court for 18 months, and the parent has failed to correct the problems which caused the child to be removed from the home. (In re Jasmon O., supra, 8 Cal.4th at pp. 419-422; Cynthia D. v. Superior Court, supra, 5 Cal.4th at pp. 254-256.) In cases of this kind, the California Supreme court has ruled that a substantial likelihood that the child will suffer serious trauma if separated from the foster family can establish sufficient detriment to overcome the parents’ right to the care, custody and companionship of the child. (In re Jasmon O., supra, 8 Cal.4th at pp. 418-419.) A child’s right to remain in a stable home is also found both to be adverse to and to outweigh a parent’s interests where a natural father failed to show a commitment to the child within a reasonable time of learning of the mother’s pregnancy, but later seeks to assert parental rights and disturb an adoptive placement or step parent family in which the child is secure and thriving. (Lehr v. Robertson, supra, 463 U.S. at pp. 261-262; Quilloin v. Walcott, supra, 434 U.S. at p. 255; Adoption of Michael H., supra, 10 Cal.4th at pp. 1054-1058.) In such cases, the United States Supreme Court has ruled that the parental rights of the natural father are superseded by policies favoring preservation of the child’s existing family unit. (Quilloin v. Walcott, supra, 434 U.S. at p. 255.)

76] Both the California Supreme Court and the United States Supreme Court have also recognized that a person’s interests and rights respecting family relationships do not necessarily depend upon the existence of a biological relationship. (Lehr v. Robertson, supra, 463 U.S. at p. 261; Adoption of Michael H.,(1995) 10 Cal.4th 1043, 1057-1058.) The United States Supreme Court has stated that “[n]o one would seriously dispute” that familial interests and rights may attach to the emotional ties which grow between members of a de facto family. (Smith v. Organization of Foster Families (1977) 431 U.S. 816, 844 [53 L.Ed.2d 14, 97 S.Ct. 2094].) Both high courts have recognized that such interests and rights may outweigh biological relationships under some circumstances. (Lehr v. Robertson, supra, 463 U.S. at p. 261; Quoilloin v. Walcott, supra, 434 U.S. at p. 255; Smith v. Organization of Foster Families, supra, 431 U.S. at pp. 843-844; Adoption of Michael H., supra, 10 Cal.4th at pp. 1057-1058.) *fn12

[77] Here, the biological parents have come before the court after having voluntarily relinquished their twin girls for adoption. The biological parents claim they are entitled to reestablish their relationship with the children, because their relinquishments of parental rights were not executed in accordance with ICWA. However, any claim which they may have under the statute does not necessarily establish a claim to that deference which parental rights are generally accorded under the Constitution. A biological parent’s constitutional rights, like other constitutional rights, may be waived, provided only that the waiver is knowingly and intelligently made (D.H. Overmyer Co., Inc. v. Frick Co. (1972) 405 U.S. 174, 185-186 [31 L.Ed.2d 124, 92 S.Ct. 775]; Tyler v. Children’s Home Society (1994) 29 Cal.App.4th 511, 545), and the counselling which is required by California law before a parent may relinquish a child for adoption has been held to be sufficient to assure that any waiver of parental rights is knowing and intelligent. (Tyler v. Children’s Home Society, supra, 29 Cal.App.3d at pp. 546-547.)

[78] Given the failure to comply with procedural requirements of ICWA, we cannot conclude that there has been a waiver of parental rights in this case. However, as we have observed, prior judicial decisions establish that, where a child has formed familial bonds with a de facto family with whom the child was placed owing to a biological parents’ unfitness (In re Jasmon O., supra, 8 Cal.4th at p. 418) or initial failure to establish a parent-child relationship (Lehr v. Roberston, supra, 463 U.S. at p. 261; Adoption of Michael H., supra, 10 Cal.4th at p. 1057), and where it is shown that the child would be harmed by any severance of those bonds, the child’s constitutionally protected interests outweigh those of the biological parents. (Lehr v. Robertson, supra, 463 U.S. at pp. 261-262; Adoption of Michael H., supra, 10 Cal.4th at pp. 1057-1058; In re Jasmon O., supra, 8 Cal.4th at pp. 418-419.) The rule can logically be no different where children have become bonded to a family in which they were placed after a knowing, intelligent and express relinquishment of parental rights. Inasmuch as children have a liberty interest in the continuity and stability of their homes (In re Jasmon O., supra, 8 Cal.4th at p. 419; In re Marilyn H., supra, 5 Cal.4th at p. 306), where a child’s biological parents knowingly and intelligently relinquish the child to others for the express purpose of giving the child a loving and stable home, the biological parents’ voluntary act constitutes at the very least a voluntary subordination of their constitutional rights to those of the children. The biological parents thus must rely solely upon ICWA for any claim which they might have in this matter.

Back to the Top

[79] The interests of the Tribe in this dispute are likewise based solely upon ICWA. There neither is nor can be any claim that the Tribe’s interests are constitutionally protected. The R’s, as the prospective adoptive parents, similarly have no interests which have been found to enjoy constitutional protection. (Smith v. Organization of Foster Families, supra, 431 U.S. at pp. 838-847.)

[80] However, the twins do have a presently existing fundamental and constitutionally protected interest in their relationship with the only family they have ever known. The children are thus the only parties before the court which have such interests. Therefore, if application of ICWA would interfere with those interests, such application must be subjected to a strict scrutiny standard to determine whether it serves a compelling government purpose and whether it is actually necessary and effective to the accomplishment of that purpose. If not, then ICWA, as so applied, would deprive the children of due process of law. (Moore v. East Cleveland, supra, 431 U.S. at p. 499; Bates v. City of Little Rock, supra, 361 U.S. at p. 524; Sherbert v. Verner, supra, 374 U.S. at p. 406.)

[81] The questions which we therefore must determine are

(1) whether the tribal interests which ICWA protects are sufficiently compelling under substantive due process standards to justify the impact which ICWA’s requirements will have on the twins’ constitutionally protected familial rights, and, if so,

(2) whether application of ICWA, under facts of the kind presented in this case, is necessary to further that interest.

[82] We have no quarrel with the proposition that preserving American Indian culture is a legitimate, even compelling, governmental interest. At the same time, however, we agree with those courts which have held that this purpose will not be served by applying the provisions of ICWA which are at issue in this case to children whose biological parents do not have a significant social, cultural or political relationship with an Indian community. It is almost too obvious to require articulation, that “the unique values of Indian culture” (25 U.S.C. Section(s) 1902) will not be preserved in the homes of parents who have become fully assimilated into non-Indian culture. This being so, it is questionable whether a rational basis, far less a compelling need, exists for applying the requirements of the Act where fully assimilated Indian parents seek to voluntarily relinquish children for adoption. The case for applying ICWA is even weaker where assimilated parents have previously concluded a reasoned and voluntary relinquishment of a child, which was valid and has become final under state law, and the child has become part of an adoptive or prospective adoptive family. In this circumstance, the invalidation of the relinquishment manifestly can serve no purpose which is sufficiently compelling to overcome the child’s fundamental right to remain in the home where he or she is loved and well cared-for, with people to whom the child is daily becoming more attached by bonds of affection and among whom the child feels secure to learn and grow. ICWA cannot constitutionally be applied under such facts.

[83] b. Equal Protection

Back to the Top

[84] ICWA requires Indian children who cannot be cared for by their natural parents to be treated differently from non-Indian children in the same situation. As a result of this disparate treatment, the number and variety of adoptive homes that are potentially available to an Indian child are more limited than those available to non-Indian children, and an Indian child who has been placed in an adoptive or potential adoptive home has a greater risk than do non-Indian children of being taken from that home and placed with strangers. To the extent this disparate and sometimes disadvantageous treatment is based upon social, cultural or political relationships between Indian children and their tribes, it does not violate the equal protection requirements of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. (United States v. Antelope (1977) 430 U.S. 641, 646 [51 L.Ed.2d 701, 97 S.Ct. 1395]; Moe v. Salish Kootenai Tribes (1976) 425 U.S. 463, 480-481 [48 L.Ed.2d 96, 96 S.Ct. 1634]; Morton v. Mancari (1974) 417 U.S. 535, 554 [41 L.Ed.2d 290, 94 S.Ct. 2474].) However, where such social, cultural or political relationships do not exist or are very attenuated, the only remaining basis for applying ICWA rather than state law in proceedings affecting an Indian child’s custody is the child’s genetic heritage — in other words, race.

[85] Equal protection principles regard racial classifications of all kinds as “inherently suspect” (Regents of the Univ. of California v. Bakke (1978) 438 U.S. 265, 289-290 [57 L.Ed.2d 750, 98 S.Ct. 2733] (lead opn. of Powell, J.)), indeed, “odious to a free people.” (Hirabayashi v. United States (1943) 320 U.S. 81, 100 [87 L.Ed. 1774, 63 S.Ct. 1375].) The United States Supreme Court has recently held that “all racial classifications, imposed by whatever federal, state, or local governmental actor, must be analyzed by a reviewing court under strict scrutiny. In other words, such classifications are constitutional only if they are narrowly tailored measures that further compelling governmental interests.” (Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena (1995) __ U.S. __ [132 L.Ed.2d 158, 182, 115 S.Ct. 2097] (hereafter “Adarand”; lead opn. of O’Connor, J.); see also Miller v. Johnson (1995) __U.S. __ [132 L.Ed.2d 762, 115 S.Ct. 2475, 2482].) The same principle applies whether the group targeted by a racial classification is burdened or benefited by the classification. (Adarand, supra, 132 L.Ed.2d at p. 179.) The foregoing principles apply to federal legislation affecting Indian affairs. (Delaware Tribal Business Commission v. Weeks (1974) 430 U.S. 73, 84 [51 L.Ed.2d 173, 97 S.Ct. 911].)

Back to the Top

[86] The Tribe and the biological parents argue that ICWA does not create a race-based classification, because application of ICWA is triggered by the child’s membership in a tribe or eligibility for membership, and depends upon the child’s genetic heritage only if the child is merely eligible for tribal membership, in which case the child must be the biological child of a tribal member. This argument is superficially appealing. However, the Tribe and the parents also argue that, under ICWA Guidelines, tribal determinations of their own membership should generally be deemed conclusive. If tribal determinations are indeed conclusive for purposes of applying ICWA, and if, as appears to be the case here, a particular tribe recognizes as members all persons who are biologically descended from historic tribal members, then children who are related by blood to such a tribe may be claimed by the tribe, and thus made subject to the provisions of ICWA, solely on the basis of their biological heritage. Only children who are racially Indians face this possibility. *fn13

[87] For purposes of determining whether a particular application of ICWA creates a racially based classification, it makes no difference that not all tribes recognize as tribal members all blood descendants of tribal members. (See, e.g., Santa Clara Pueblo v. Martinez (1978) 436 U.S. 49, 52-53 [56 L.Ed.2d 106, 98 S.Ct. 1670] [tribe denied tribal membership to the children of female tribal members who married outside the tribe, but not to the children of similarly situated male tribal members].) As we have observed above, to the extent that tribal membership within the meaning of ICWA is based upon social, cultural or political tribal affiliations, it meets the requirements of equal protection. However, any application of ICWA which is triggered by an Indian child’s genetic heritage, without substantial social, cultural or political affiliations between the child’s family and a tribal community, is an application based solely, or at least predominantly, upon race and is subject to strict scrutiny under the equal protection clause. So scrutinized, and for the same reasons set forth in our discussion of the due process issue, it is clear that ICWA’s purpose is not served by an application of the Act to children who are of Indian descent, but whose parents have no significant relationship with an Indian community. If ICWA is applied to such children, such application deprives them of equal protection of the law.

[88] c. The Indian Commerce Clause and the Tenth Amendment

Back to the Top

[89] Congress’s authority to enact ICWA arises from clause 3 of section 8 of article I of the Constitution, “The Congress shall have power . . . to regulate Commerce . . . with the Indian tribes.” (25 U.S.C.A. Section(s) 1901, subd. (1); In re Wanomi P., supra, 216 Cal.App.3d at pp. 162-163.) This clause grants Congress plenary power over Indian affairs. (United States v. Wheeler (1978) 435 U.S. 313, 318 [55 L.Ed.2d 303, 98 S.Ct. 1079]; Morton v. Mancari, supra, 417 U.S. at pp. 551-552; Worcester v. State of Georgia (1831) 31 U.S. (6 Pet. ) 515, 559 [8 L.Ed. 483].) Indian tribes are deemed to be semi-sovereign nations under the protection of the federal government. Tribes retain attributes of sovereignty over both their members and their territories; such sovereignty is dependent on, and subordinate to, only the Federal Government, not the states. (California v. Cabazon Band of Indians (1987) 480 U.S. 202, 207 [94 L.Ed.2d 244, 107 S.Ct. 1083]; Washington v. Confederated Tribes (1980) 447 U.S. 134, 153-154 [65 L.Ed.2d 10, 100 S.Ct. 2069].)

[90] The principles of tribal self-government, grounded in notions of inherent sovereignty and in congressional policies, seek an accommodation between the interests of the tribes and the federal government on the one hand, and those of the states, on the other. (Washington v. Confederated Tribes, supra, 447 U.S. at pp. 156-157.) Thus, the Supreme Court has held nonreservation Indians are generally subject to nondiscriminatory and generally applicable state laws “[a]bsent express federal law to the contrary.” (Mescalero Apache Tribe v. Jones (1973) 411 U.S. 145, 148-149 [36 L.Ed.2d 114, 93 S.Ct. 1267].) Even on Indian reservations, state laws generally may be applied insofar as they do not interfere with reservation self-government or essential internal tribal affairs, or impair a right reserved by federal law. (Id. at p. 148.)

[91] Jurisdiction over matters of family relations is traditionally reserved to the states. (Rose v. Rose (1987) 481 U.S. 619, 625 [95 L.Ed.2d 599, 107 S.Ct. 2029]; Lehman v. Lycoming County Children’s Services (1982) 458 U.S. 502, 511-512 [73 L.Ed.2d 928, 102 S.Ct. 3231]; In re Burris (1890) 136 U.S. 586, 593-594 [34 L.Ed. 500, 10 S.Ct. 850].) Thus, where it is contended that a federal law must override state law on a matter relating to family relations, it must be shown that application of the state law in question would do “`major damage’ to `clear and substantial federal interests.’ [Citations].” (Rose v. Rose, supra, 481 U.S. at p. 625.)

Back to the Top

[92] Under these principles, ICWA should apply rather than state laws respecting family relations only where such application actually serves the specific purposes for which ICWA was enacted, “to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families” (25 U.S.C. Section(s) 1902), or the broader purposes which are served by all authorized exercises of Congressional power under the Indian Commerce Clause, namely, the purposes of acting as a guardian to the Indian tribes, and in so doing, protecting Indian tribal self-government. (Morton v. Mancari, supra, 417 U.S. at pp. 553-554.)

[93] The recent case of United States v. Lopez ___ U.S. ___ [131 L.Ed.2d 626, 115 S.Ct. 1624] is instructive, although that case concerned the powers of Congress under the Interstate Commerce Clause, and the reach of the Indian Commerce Clause is not identical. In Lopez, the United States Supreme Court indicated that Congress’s power under the Interstate Commerce Clause to legislate in areas otherwise reserved to the states will be confined to matters which substantially affect interstate commerce. (115 S.Ct. at p. 1630.) The reasoning of Lopez logically applies with respect to the Indian Commerce Clause, indeed, to any enumerated power of Congress. Congress exceeds its authority when, acting under any of its enumerated powers, Congress legislates in matters generally within the jurisdiction of the states, in the absence of an adequate nexus to the enumerated power under which the legislation is enacted. (Cf. 115 S.Ct. at pp. 1631-1634.)

[94] No such nexus exists respecting application of ICWA to children whose families do not maintain significant relationships with an Indian tribe or community or with Indian culture. Once again, ICWA’s purpose simply is not furthered by an application of the Act to families who are of Indian descent, but who maintain no significant social, cultural or political relationships with Indian community life, and are in all respects indistinguishable from other residents of the state. Thus, if ICWA is applied to such children, that application impermissibly intrudes upon a power reserved to the states.

Back to the Top

[95] d. Conclusion

[96] We do not believe ICWA applies only to Indian children who are domiciled on reservations. Indeed, the Act’s express terms provide for application of most of its provisions to reservation-domiciled and nonreservation-domiciled Indians alike. (Section(s) 1911, subds. (b) and (c).) Only the provision for exclusive jurisdiction in the tribal court is restricted to reservation domicilaries. (Section(s) 1911, subd. (a).) However, if the Act applies to children whose families have no significant relationship with Indian tribal culture, such application runs afoul of the Constitution in three ways:

(1) it impermissibly intrudes upon a power ordinarily reserved to the states,

(2) it improperly interferes with Indian children’s fundamental due process rights respecting family relationships; and

(3) on the sole basis of race, it deprives them of equal opportunities to be adopted that are available to non-Indian children and exposes them, like the twin girls in this case, to having an existing non-Indian family torn apart through an after the fact assertion of tribal and Indian-parent rights under ICWA (which rights were, in this case, specifically and intentionally ignored by the biological parents now asserting them). All of this occurs in the absence of even a rational relationship to a permissible state purpose, much less a necessary connection with a compelling state purpose.

[97] We conclude that principles of substantive due process, equal protection and federalism all carry the same implication regarding the proper scope of ICWA — it can properly apply only where it is necessary and actually effective to accomplish its stated, and plainly compelling, purpose of preserving Indian culture through the preservation of Indian families. We agree with those courts which have held that ICWA’s purpose is not served by an application of the Act where the child may be of Indian descent, but where neither the child nor either parent maintains any significant social, cultural or political relationships with Indian life.

(See these Constitutional arguments also on our 14th Amendment page – CAICW)

Back to the Top

[98] 4. The Trial Court Must Determine The Question Of Whether There Was An “Existing Indian Family” Which Is The Factual Predicate To The Application Of ICWA

[99] The trial court in this case determined, as a matter of law, that the twins are Indian children, because they are enrolled members of the Tribe, are recognized by the Tribe as members and are the biological children of an enrolled and recognized tribal member. The trial court thus concluded that ICWA applies, and the biological parent’s relinquishment of the twins for adoption was invalid under section 1913 of the Act. However, more is required to justify an application of ICWA than a biological parents’ mere formal enrollment in a tribe, or a self-serving after-the-fact tribal recognition of such a parent’s membership. Such token attestations of cultural identity fall short of establishing the existence of those significant cultural traditions and affiliations which

[100]ICWA exists to preserve, and which are consequently necessary to invoke a constitutionally permissible application of the Act. *fn14

[101] Because the trial court was persuaded that enrollment in the Tribe and tribal recognition of the twins’ tribal membership were enough to trigger the application of ICWA, the court had no occasion to make a further factual determination as to whether the biological parents maintain significant social, cultural or political relationships with the Tribe. The case must therefore be remanded so that such factual determination can be made.

[102] The biological parents (and the Tribe), of course, will bear the burden of proof on this issue. It is they who seek to set aside the relinquishment of parental rights which were otherwise final and binding under California law. To do this they rely on the application of a federal statute. It is they who must prove that the necessary factual basis for the application of that statute is present. (Evid. Code, Section(s) 500.)

[103] Moreover, that determination must focus upon the biological parents’ social, cultural and political relationship with the Tribe, although any relationship between the Tribe and extended family members may well bear on the issue of the biological parents’ relationship. On this point, we agree with the Supreme Court of South Dakota, writing in Claymore v. Serr, supra, 405 N.W.2d 650, one of the early cases to apply the existing Indian family doctrine. The Claymore court observed that ICWA refers in some contexts to “Indian families” and in others, to “extended Indian families,” suggesting that when the former term is used, the nuclear family, “the fundamental social unit in civilized society,” is intended. (405 N.W.2d at pp. 653-654.)

[104] The biological parents and the Tribe contend it would be unfair to focus only upon the nuclear family when assessing an application of ICWA, because such focus would ignore tribal kinship systems, in which the extended family is a fundamental unit. The parents and Tribe argue that one of the primary reasons ICWA was enacted was to combat the adverse effects upon Indian communities of failures by state courts and agencies to appreciate the importance in tribal life of the extended family, as well as other customs and institutions affecting the welfare of Indian children. They thus argue, in effect, that to exclude the extended family from consideration when we determine whether there is an existing Indian family, and hence, whether ICWA applies, would be a mere analytical sleight of hand, by which ICWA’s requirements of giving due consideration to essential tribal relations would be unfairly sidestepped.

[105] After giving this argument long and careful consideration, we are compelled to disagree. First, it implicitly assumes the conclusion that the biological parents did have significant social, cultural or political connections to the Tribe. If they had no such connections, then there would be no real issue of an “extended Indian family” for the court to ignore. Secondly, and more significantly, it must not be forgotten that this case has arisen because the biological parents abjured their Indian heritage when, instead of turning to their extended family for succour and support in anticipation of the twins’ birth, they voluntarily, and for rational and understandable reasons, relinquished those children to strangers. Then, to prevent interference with those relinquishments by the Tribe, they denied their heritage in response to multiple direct inquiries. Having done these things, the biological parents may now justly be required to prove that they themselves have a significant relationship with an Indian community and may be precluded from using cultural ties which may be maintained by their blood relatives to bootstrap themselves into an application of ICWA.

[106] The determination whether the twins were removed from an existing Indian family must also be made as of the time of the relinquishments. There can be no justification or excuse for tearing children from a family to which they are bonded, based upon an ex post facto manufacture of a legal basis for applying ICWA. The R’s urge us to hold that contemporaneous enrollment in the tribal register is necessary to establish that a child’s biological parent is a member of an Indian tribe within the meaning of ICWA. While such a bright-line rule has much to recommend it, we can imagine circumstances in which it would work an injustice, and we decline to announce such a rule. Nevertheless, the circumstance that Richard’s mother Karen — not Richard himself — applied for tribal enrollment for herself, Richard and all his children after the present dispute arose is a circumstance which can be considered in determining whether Richard truly maintained a significant relationship with the Tribe at the time of the twins’ birth.

[107] In considering whether the biological parents maintained significant ties to the Tribe, the court should also consider whether the parents privately identified themselves as Indians and privately observed tribal customs and, among other things, whether, despite their distance from the reservation, they participated in tribal community affairs, voted in tribal elections, or otherwise took an interest in tribal politics, contributed to tribal or Indian charities, subscribed to tribal newsletters or other periodicals of special interest to Indians, participated in Indian religious, social, cultural or political events which are held in their own locality, or maintained social contacts with other members of the Tribe. In this regard, we find particularly significant the fact that in the months preceding the birth of the twins, the biological parents turned not to the Tribe or even to other family members, *fn15 but rather to California’s legal process for the purpose of securing the adoption of the twins by a loving family able to care for them. The biological parents did this voluntarily and for reasons which reflected that their primary concern was for the twins’ future welfare. Moreover, as already noted, in order to facilitate the adoption process the biological parents expressly and intentionally denied their Indian heritage. Such conduct permits a very strong inference to be drawn about the absence of a significant relationship with the Tribe.

Back to the Top

[108] 5.If the Trial Court Finds That ICWA Applies, Then a Further Hearing Must Be Held on Whether a Change of Custody Would Be Detrimental to the Twins.

[109] In anticipation of the possibility that the trial court might, upon remand, conclude that ICWA does apply, the R’s have filed, and there is now pending in the trial court, a petition for their appointment as guardians of the twins. *fn16 The biological parents and the Tribe dispute that such a procedure is appropriate. *fn17 The R’s respond that a hearing on their guardianship petition is required in order to protect the constitutional rights of the twins and, in any event, is not precluded by the provisions of ICWA. *fn18

[110] However, the biological parents and the Tribe contend that, if the trial court ultimately finds that ICWA applies, then

(1) the relinquishments of parental rights would be invalid,

(2) no basis for an involuntary termination of rights would exist and

(3) the twins would have to be returned to the biological parents, without further proceedings. In support of this contention, they cite ICWA sections 1913, subdivision (c), and 1920, as well as Family Code sections 8804 and 8815 and two California cases, In re Timothy W. (1990) 223 Cal.App.3d 437 and In re Cheryl E. (1984) 161 Cal.App.3d 587.

[111] The California authorities cited are inapposite. Family Code sections 8804 and 8815 are part of the statutory scheme governing independent adoptions and have no application outside of that scheme. *fn19 For the same reason, In re Timothy W., supra, has no application to this case. In Timothy W., the court held that under the Civil Code statutes which formerly governed independent adoptions, a parent who withdrew consent to an adoption within six months was entitled to have the child returned without the need for judicial findings on the child’s best interests. (223 Cal.App.3d at p. 441.) In re Cheryl E., supra, is also distinguishable. In that case, the Court of Appeal affirmed a trial court order granting the mother’s petition to rescind her relinquishment of parental rights on the ground of fraud and undue influence (161 Cal.App.3d at p. 594); the appellate court found there was no occasion in the rescission action for the child’s best interests to be considered, and noted that this issue would be addressed in a separate dependency proceeding, which was pending. (Id. at pp. 603-604.)

[112] The contention that ICWA, section 1913, subdivision (c), requires automatic return of the children to the biological parents has somewhat more force. That section provides that “[i]n any voluntary proceeding for termination of parental rights to, or adoptive placement of, an Indian child, the consent of the parent may be withdrawn for any reason at any time prior to the entry of a final decree of termination or adoption, as the case may be, and the child shall be returned to the parent.” (Italics added.) If ICWA applies in this case, then no valid decree or other document effecting a termination of parental rights has been entered, and the biological parents have long since withdrawn their consent. Thus, the Tribe argues, section 1913, subdivision (c), requires the immediate and unconditional return of the children to their biological family.

[113] We disagree. The reach of section 1913 is limited by the twins’ interest in having a stable and secure home which, as we have already concluded, is an interest of constitutional dimension. Inasmuch as an individual’s interests in matters of family life are “compelling and are ranked among the most basic of civil rights” (Quilloin v. Walcott, supra, 434 U.S. at p. 255), and inasmuch as children “are not simply chattels belonging to the parent,” but have fundamental, constitutionally protected interest of their own, including “the fundamental right to . . . have a placement that is stable [and] permanent” (In re Jasmon O., supra, 8 Cal.4th at p. 419), we believe it would constitute a violation of the Due Process Clause of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to remove a child from a stable placement, based upon statutory violations which occurred in making the placement, without a hearing to determine whether the child would suffer harm if removed from that placement. (Stanley v. Illinois, supra, 405 U.S. at p. 649.) Such a constitutional mandate cannot be avoided by reliance on the statutory provisions of ICWA.

[114] However, even under ICWA a change of custody hearing can be justified. Most of its provisions which deal with the custody of children expressly provide that consideration must be given to the child’s interests before any order changing a child’s custody is made. For example, section 1916, subdivision (a), deals with the issue of return of custody in circumstances substantially like those presented here. *fn20 It speaks directly to what happens after “a final decree of adoption of an Indian child has been vacated.” We do not have that precise situation here; however, we do have something very close: the invalidation of a voluntary relinquishment of parental rights. In both situations, custody of the child would in all likelihood have been given over to the prospective adoptive parents prior to any determination of invalidity. If, because of the application of ICWA, a final adoption is invalidated, or, as in this case, made impossible, the problem is the same: what is to be done about custody? Section 1916, subdivision (a), contemplates and provides something very similar to the procedure which we will require here in the event that the trial court finds that ICWA applies to this case.

[115] Two other sections of ICWA also recognize the importance of the child’s interests and needs. Section 1915 provides preferences for the placement of Indian children, but authorizes a different placement if there is good cause and specifically requires that any special needs of the child be considered in making a placement. (Section(s) 1915, subds. (a) and (b).) Section 1915, subdivision (c) authorizes a child’s tribe to specify different preferences, but requires any placement so specified to be “the least restrictive setting appropriate to the particular needs of the child.” Section 1920, which prescribes the consequences of an improper removal of a child from the legal custodian, and which the Tribe and biological parents contend requires automatic return of the child, provides that such return need not be ordered if it would subject the child to substantial and immediate danger, or the threat thereof.

[116] In the context of these express provisions within ICWA for consideration of the child’s interests in making a custody order, it does no violence to the overall statutory scheme to imply such a provision where it is contended that a child’s custody must be changed pursuant to section 1913, subdivision (c), due to a violation of section 1913, subdivision (a). *fn21 This result is not inconsistent with the intent of Congress. The legislative history of ICWA reflects the following comment in the House Report of the Interior and Insular Affairs Committee of July 24, 1978: “[T]he committee notes that nothing in those subsections [referring to the subsections of section 1913] prevents an appropriate party or agency from instituting an involuntary proceeding, subject to section [1912], to prevent the return of the child, but does not wish to be understood as routinely inviting such actions.” (1978 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News, at p. 7546; italics added.) *fn22

Back to the Top

[117] Finally, there is significant case authority for such a custody hearing. The R’s and amicus curiae have cited authorities from Colorado, New Jersey and New Mexico, in which the courts recognize that, where an anticipated adoption cannot legally be effected, the child’s interests must nevertheless be considered before custody of the child is returned to the biological parent. (See Matter of Custody of C.C.R.S. (Colo. 1995) 892 P.2d 246, 257-258, cert. denied by C.R.S. v. T.A.M. (1995) ___ U.S. ___ [133 L.Ed.2d 69, 116 S.Ct. 118]; Matter of Adoption of J.J.B. (1995) 119 N.M. 638 [894 P.2d 994, 1008-1009] cert. denied by Bookert v. Roth (1995) ___ U.S. ___ [133 L.Ed.2d 110, 116 S.Ct. 168]; Sorentino v. Family Children’s Soc. of Elizabeth (1976) 72 N.J. 127 [367 A.2d 1168, 1170-1171].) The California Supreme Court has also suggested in dictum that where a parent, having the right to do so, vetoes an anticipated adoption, the question of whether custody of the child should be awarded to the parent is a matter for separate determination. (Adoption of Kelsey S., supra, 1 Cal.4th at p. 851 [“Even if petitioner has the right to withhold his consent (and chooses to prevent the adoption), there will remain the question of the child’s custody”].) The Alaska Supreme Court reached the same conclusion in a case involving ICWA. In A.B.M. v. M.H., supra, 651 P.2d 1170, cert. denied by Hunter v. Maxie (1983) 461 U.S. 914 [77 L.Ed.3d 283, 103 S.Ct. 1893] the adoption of an Indian child was vacated owing to certain statutory violations, and thereafter, the mother petitioned to have the child returned to her custody. (651 P.2d at pp. 1171-1172.) The Alaska Supreme Court held that a hearing on the issue of custody would be required, subject to the provisions of ICWA, section 1912, before a return to the mother could be ordered. (Id. at pp. 1175-1176.)

[118] We therefore hold that, if the trial court determines upon remand that

(1) ICWA applies in this case, and

(2) under ICWA, the voluntary termination of the parental rights of the biological parents is invalid, the court must nevertheless hold a hearing on the question of whether there should be a change of custody. That can best be accomplished in the context of the R’s petition to be appointed guardians of the twins.

[119] California’s guardianship law offers equitable and constitutionally permissible standards for resolving the question of the proper custody of the twins in the event their pending adoption by the R’s fails due to the application of ICWA. These standards look to something more than the twins’ “best interests,” but rather require an examination of whether a custody change will result in detriment to them. These standards are consistent with the statutory preferences for maintaining a child’s custodial ties with the biological parents, but do not require that result if the evidence shows that the child would be harmed if removed from the custody of those persons who have acted as de facto and psychological parents since birth and with whom the child has bonded. *fn23

[120] Such guardianship hearing must be held under the provisions of Probate Code, section 1514, Family Code, sections 3040 and 3041, and ICWA, section 1912, subdivision (e). The burden of proof will necessarily rest upon the R’s. (Evid. Code, Section(s) 500.) The twins shall not be returned to the custody of the biological parents and may instead remain with the R’s if, and only if, the R’s can establish, by clear and convincing evidence, including the testimony of qualified expert witnesses, that a change of custody to the biological parents would be detrimental to the twins, and a grant of custody to the R’s is necessary to serve the twins’ best interests. (Fam. Code, Section(s) 3040, 3041; 25 U.S.C. Section(s) 1912, subd. (e); In re B.G. (1974) 11 Cal.3d 679, 695; In re Phillip B. (1983) 139 Cal.App.3d 407, 421.) *fn24 In making this determination, the court should take into consideration the likelihood, or lack thereof, that the twins will suffer trauma if separated from the R’s. *fn25

[121] The court will not be precluded from granting the guardianship petition because of any alleged failure to provide remedial and rehabilitative services to the biological parents, as provided in ICWA section 1912, subdivision (d). ICWA requires such services “to prevent the breakup of the Indian family.” The only time at which the “breakup” of the twins’ biological family could have been “prevented” was before the voluntary relinquishments which were made in this case. At that time, as we have already noted, the biological parents were counseled as required by California law (Fam. Code, Section(s) 8621 and regulations adopted thereunder [Cal. Code Regs., tit. 22, Section(s) 35128 et seq]), concerning the relinquishment and adoption process, alternatives to adoption, resources for financial assistance, employment resources, child care resources, housing resources and health service resources which were available to them if they determined not to relinquish their children. Despite such counselling, the parents decided, for good and sufficient reasons, to relinquish the children for adoption. We believe these circumstances adequately establish that active efforts were made to prevent the breakup of the family as required by ICWA section 1912, subdivision (d), and that such efforts were unsuccessful.

Back to the Top

[122] CONCLUSION