By Elizabeth S. Morris

A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Helms School of Government in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in Public Policy

https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/masters/591

‘Although the ICWA has some statutory safeguards to prevent misuse, numerous families continue to be hurt by the law.’

Preface

My husband and I began our lives together in a symbiotic alcoholic-enabler relationship in the late 70’s. With our family on the edge of self-destruction in 1987, my husband, an enrolled member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, born and raised on the Leech Lake reservation, had a transformational experience which changed his worldview and led him to take our family in a new direction.

Having watched many of his relatives suffer within the reservation system, he began to see reservation violence and crime as an outcome of current federal Indian policy more than it was about past policy. This led us to forming an advocacy in the late 90’s for families hurt by federal Indian policy. We did our best to share hope and life, as inadequate as we were, by assisting extended family in our home, neighbors in our community, and strangers across the nation. We never did it for money; there was never any money. Everything we did came from passion for the lives of our children, nieces and nephews, and extended communities.

Unfortunately, reservation crime, corruption, drug abuse and violence have continued to increase over the years. My husband has since passed away and I am a widow, continuing the work we had begun in 1996.

This thesis compiles some of the documented history, philosophy, and consequences of federal Indian policy. It also includes a preliminary quantitative causal comparative survey with 1351 participants – 551 of whom identify tribal heritage – and explores the relationship between differences.

We serve a powerful God with whom all things are possible. Our job is to serve in the capacity He has given us, even if we do not understand why, and then enjoy watching what He does next.

Abstract

This paper will examine the philosophical underpinnings of current federal Indian policy and its physical, emotional, and economic consequences on individuals and communities.

The U.S. Civil Rights Commission found in 1990 that “[T]he Government of the United States has failed to provide civil rights protection for Native Americans living on reservations” (W. B. Allen 1990, 2). As Regan (2014) observes, individuals have been denied full title to their property – and thus use of the property as leverage to improve their economic condition (Regan 2014). Tribal executive and judicial branches have been accused of illegal search and seizures, denial of right to counsel or jury, ex parte hearings and violations of due process and equal protection (W. B. Allen 1990, 3). Violence, criminal activity, child abuse and trafficking are rampant on many reservations (DOJ 2018). Largely because of crime and corruption, many have left the reservation system. The last two U.S. censuses’ report 75% of tribal members do not live in Indian Country (US Census Bureau 2010).

Research suggests current federal Indian policy and the reservation system are built on philosophies destructive to the physical, emotional and economic health of individual tribal members. This paper contends that allowing property rights for individual tribal members, enforcing rule of law within reservation systems, supporting law enforcement, and upholding full constitutional rights and protections of all citizens would secure the lives, liberties and properties of affected individuals and families.

Introduction

For almost 200 years the U.S. federal government has claimed wardship over members of federally recognized Indian tribes. Yet, despite the nineteenth century U.S. federal court rulings that propagated this view, disagreement continues as to whether tribes located within the United States are sovereign, whether Congress has plenary power over them, and whether individual tribal members have U.S. Constitutional rights:

- Some say the nineteenth century U.S. Supreme Court cases known as the ‘Marshall Trilogy’ contradict tribal sovereignty. Others say they uphold it.

- Some say treaties promise a permanent trust relationship. Others point out that most treaties have clearly specified final payments of federal funds and benefits and were written and signed with clear intent for gradual assimilation.

- Some say the Constitution never gave Congress anything more than the power to regulate trade with tribes. Others claim the Constitution not only gave Congress total and exclusive plenary power to decide every aspect of life in Indian Country – but by unstated extension, gave the executive branch this power as well.

- Some argue that the Constitution never had authority over tribes or tribal members. Others cite the Constitution when seeking judicial redress.

- Some tribal officials argue that international law should not have been forced upon non-European cultures that had no say in it. Others point to natural law and international law – the grounds for treaties between nations – as basis for uninterrupted tribal sovereignty.

Inherent, retained tribal sovereignty was reality for tribal governments prior to the formation of the United States and in the immediate years following its birth, but is not reflected in case law from the 1800s and much of the 1900s. By the time of Andrew Jackson, the United States had taken a position of control. Further, over the last two centuries, the vast majority of tribal leaders accepted large payments for land, accepted federal trust benefits, and submitted to federal government’s de facto power over them.

Throughout history and every heritage, various men have coveted power over others. Today, tribal governments, while accepting and playing into Congress’ claim of plenary power, have themselves, also, claimed exclusive jurisdiction and authority over unwilling citizens. Tribal governments regularly lobby and petition both Congress and the White House to codify tribal jurisdiction over the lives, liberty and property of everyone within reservation boundaries as well as some outside reservation boundaries. While claiming exclusive jurisdiction, tribal governments have requested and given blessing for the federal government to manage children of tribal heritage – asking Congress to write the Indian Child Welfare Act and the executive branch to write federal rules governing the placement of every enrollable child in need of care. Some tribal governments and supportive entities have gone further – asking even governors and state legislators to expand on and strengthen control over children with heritage.

Often cited as justification for the ICWA is a 1998 pilot study by Carol Locust, a training director at the Native American Research and Training Center at the University of Arizona College of Medicine. Locust’s study is said to have shown that “every Indian child placed in a non-Indian home for either foster care or adoption is placed at great risk of long-term psychological damage as an adult” (Locust, Split Feather Study 1998). Referring to the condition as the “Split-feather Syndrome,” Locust claims to have identified “unique factors of Indian children placed in non-Indian homes that created damaging effects” (Locust, Split Feather Study 1998). The Minnesota Department of Human Services noted “an astonishing 19 out of 20 Native adult adoptees showed signs of “Split-feather syndrome” during Locust’s limited study (DHS 2005).

“Unfortunately,” according to Bonnie Cleaveland, PhD ABPP, “the study was implemented so poorly that we cannot draw conclusions from it.” Only twenty adoptees with tribal heritage – total – were interviewed. All were removed from their biological families and placed with non-native families. There were no control groups to address other variables. According to Cleaveland:

Locust asserts that out-of-culture removal causes substance abuse and psychiatric problems. However, she uses no control group. She doesn’t acknowledge the high rates of trauma, psychiatric and substance abuse among AI/AN people who remain in their culture and among the population of foster children. These high rates of psychosocial problems could easily account for all of the symptoms Locust found in her subjects

(Cleaveland 2015).

Cleaveland concluded, “Sadly, because many judges and attorneys, and even some caseworkers and other professionals, are not familiar with the research, results that may be very wrong are leading to the wrong outcomes for children” (Cleaveland 2015). While supporters of ICWA cite “Split-feather Syndrome” as proof the ICWA is in the best interest of children, many children have been hurt by application of the law.

Questions that need more extensive study include whether children who were adopted into non-Indian families as children show greater problems with self-identity, self-esteem, and inter-personal relationships than do their peers. Are the ties between children who have tribal heritage and their birth families and culture stronger than that of their peers, no matter the age at adoption? Other considerations include whether all tribal members support federal policies that mandate their cases be heard only in tribal courts and whether a percentage of persons of tribal heritage believe federal Indian policy infringes on their life, liberty and property.

The central concern of this paper is how current federal Indian policy has affected the lives, liberty and property of those who have tribal heritage – most specifically the Indian Child Welfare Act. Through research of the historical foundations of federal Indian policy and a nation-wide comparative survey of family dynamics, this paper will attempt to answer these and other questions.

READ FULL TEXT – https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/masters/591

Citation

Morris, Elizabeth S. The Philosophical Underpinnings and Negative Consequences of the Indian Child Welfare Act. Master Thesis, Helms School of Government, Liberty University, Lynchburg: Digital Commons, 2019, 337.

—————————-

References

Aziz G. Sayigh, Boris V. Babson, A.S. Erickson, Charles S. Dameron, Adam I.W. Schwartzman, Nicholas P. Desatnick. “The Storied History of Dartmouth.” The Dartmouth Review, 10 2006.

25 U.S Code. “15 § 1302.” 1968.

Ablavsky, Gregory. “Beyond the Indian Commerce Clause.” Yale Law Journal 124 (2015): 1012, 1017.

Abourezk, James G. THE OCCUPATION OF WOUNDED KNEE, 1973 – American Indian Movement. House of Representatives, Wounded Knee: U.S. Government, 1972.

ACF. Tribal Child Counts. Washington DC: Child Care Bureau, Office of Family Assistance, 2007.

Adoption of Baby Boy L. No. 53,592 (Kansas Supreme Court, April 3, 1982).

Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl. No. 12–399 (U.S. Supreme Court, June 25, 2013).

Ahrens, Kym R., Michelle M. Garrison, and Mark E. Courtney. “Health Outcomes in Young Adults From Foster Care and Economically Diverse Backgrounds.” American Academy of Pediatrics, 2014: 10.

AIPRC. American Indian Policy Review Commission Final Report, Vol. I. report to provide foundation for understanding of federal Indian policy, law, and history, American Indian Policy Review Commission,, Congress, Washington DC: GPO; Eric.Ed.gov, 1977, 593.

Allen, William B. Commissioner. The Indian Civil Rights Act: United States Commission on Civil Rights Statement. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, U.S. Congress, Washington DC: USCCR, 1990, 16.

Allen, William B. “Email Correspondence.” June 8, 2018.

—. “ICWA Teach-in, Keynote.” Washington DC: CAICW, 10 2010.

Allen, William. Review of Federal Indian Policy. Havre d’ Grace, MD: Unpublished, 2010, 25.

Allison Randall, Chief of Staff. “Baaken violence.” DOJ/Office on Violence Against Women. washington DC: DOJ, 9 13, 2013.

Ambrose, of the St John Indians. “Speech at a Conference Held at Watertown, in the Colony of Massachusetts-Bay July 12, 1776.” Edited by Peter Force. American Archives. Ser.5 v.1 ([1776] 1837–53): 839.

Arkes, Hadley. “The Natural Law Challenge.” Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy (Harvard Society for Law and Public Policy, Inc) 36, no. 3 (Summer 2013): 961-975.

Attorney General’s Advisory Committee. Committee on American Indian and Alaska Native Children Exposed to Violence: Ending Violence so Children can Thrive. Final Full Report, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, Office of Justice Programs, Deptartment of Justice, Washington DC: Dept. of Justice, 2014, 257.

Avalon Project. “Treaties Between the United States and Native Americans.” Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. 2008. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/ntreaty.asp (accessed June 22, 2016).

Banner, Stuart. How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier. 2nd. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2007.

Bastiat, Fredrick. The Law. New York: The Foundation for Economic Education, 1998.

Bellamy, Jennifer L., Geetha Gopalan, and Dorian E. Traube. “A National Study of the Impact of Outpatient Mental Health Services for Children in Long Term Foster Care.” Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry (University of Chicago) 15, no. 4 (2010): 467-79.

Bender, Albert. “South Dakota Commits Shocking Genocide Against Native Americans by Abducting Their Children.” ICWA INFO. Edited by Native American Rights Foundation. Native American Rights Foundation. February 20, 2015. http://icwa.narf.org/news/1747 (accessed June 22, 2016).

Benedict, Jeff. Without Reservation. New York: Harper, 2000.

Bernholz, Charles D., Laura K. Weakly, Brian L. Pytlik Zillig, and Karin Dalziel. “As long as grass shall grow and water run: The treaties formed by the Confederate States of America and the tribes in Indian Territory, 1861.” Treaties Portal. Love Memorial Library. n.d. http://treatiesportal.unl.edu/csaindiantreaties/.

BIA. Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). 2019. https://www.bia.gov/bia (accessed 4 16, 2019).

—. “Indian Child Welfare Act Proceedings.” Federal Register, June 14, 2016: 369.

—. FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS. 9 2, 2016. http://www.bia.gov/FAQs/ (accessed Sept 3, 2016).

—. “ICWA Guidelines teleconference.” NWX-DEPT OF INTERIOR-NBC (US). Washington DC: Department of Interior, 2015. 1-114.

—. “Indian Child Welfare Act.” US Deptartment of the Interior: Indian Affairs. June 8, 2016. http://www.indianaffairs.gov/WhoWeAre/BIA/OIS/HumanServices/IndianChildWelfareAct/index.htm (accessed June 8, 2016).

BIA. Indian Entities Recognized and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs. Notice, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Department of Interior, DC: Federal Government, 2003, 68180 -68184 (5 pages).

Bickel, Alexander M. “Citizenship in the American Constitution.” Faculty Scholarship Series, 1973.

Bird, Allyson. Broken Home: The Save Veronica story. News Article, Charleston: Charleston City Paper, 2012.

Black, Henry Campbell. Black’s Law Dictionary Free. 2. The Law Dictionary, 2018.

Blackstone, William. Blackstone’s Commentaries. Philadelphia: William Young Birch and Abraham Small, 1803.

Bolick, Clint. “Native American Children: Separate But Equal?” Hoover Institution. Oct 27, 2015. http://www.hoover.org/research/native-american-children-separate-equal (accessed July 27, 2016).

Bordewich, Fergus M. Killing the White Man’s Indian: Reinventing Native Americans at the End of the Twentieth Century. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, 1996.

Bouvier, John. A Law Dictionary, Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States and of the Several States of the American Union. 6. J.B. Lippincott & Company, 1856.

Bowdoin, James. “To George Washington from James Bowdoin, 30 July 1776.” Founders Online – National Archives. Edited by Philander D. Chase. University Press of Virginia. July 30, 1776. http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0378 (accessed 9 24, 2018).

Brackeen v Zinke. 4:17-cv-00868-O (US District Court, Northern District Of Texas, Fort Worth Division, 10 4, 2018).

Braund, Kathryn. “Summer 1814: The Treaty of Ft. Jackson ends the Creek War.” National Park Service. 8 15, 2017. https://www.nps.gov/articles/treaty-of-fort-jackson.htm (accessed 3 11, 2019).

Brief for Amicus Curiae of Thomas Lee Morris, Elizabeth S. Morris and Roland J. Morris, Supporting Respondent. 03-107 (United States v. Billy Jo Lara, On Writ of Certiorari, December 15, 2003).

Brief of Amicus Curiae Christian Alliance for Indian Child Welfare in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellees and Affirmation (Brackeen v. Zinke, 2018). 4:17-CV-00868 (U.S. Court of Appeals for 5th Circuit, February 2019).

Brief of Amicus Curiae Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation in Support of the Respondent. 16-1498 (Supreme Court of the United States, Oct 30, 2018).

Brown, Thomas. “Did the U.S. Army Distribute Smallpox Blankets to Indians? Fabrication and Falsification in Ward Churchill’s Genocide Rhetoric.” Plagiary: Cross‐Disciplinary Studies in Plagiarism, Fabrication, and Falsification, 2006: 100-129.

CAICW. “Administrator.” Letters from Families. Ronan: Christian Alliance for Indian Child Welfare, June 9, 2004.

—. “Administrator.” Growing Crime, Changing Dynamics. Fargo: Christian Alliance for Indian Child Welfare, June 27, 2014.

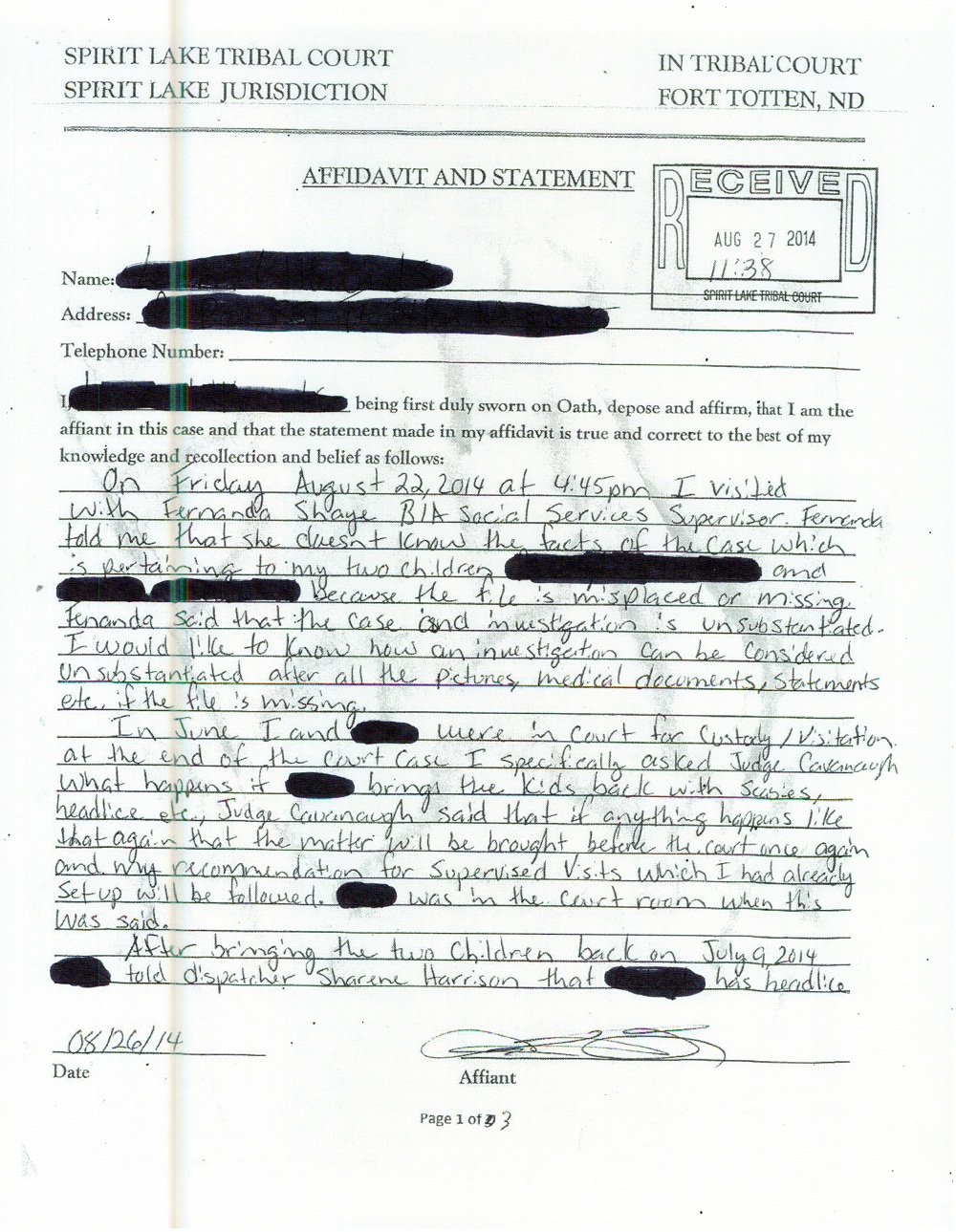

—. “Testimony from the Christian Alliance for Indian Child Welfare to the House Subcommittee on Indian and Alaska Native Affairs: Child Protection and the Justice System on the Spirit Lake Indian Reservation.” CAICW.org. June 24, 2014.

TESTIMONY: CHILD PROTECTION AND THE JUSTICE SYSTEM ON THE SPIRIT LAKE INDIAN RESERVATION:(accessed May 19, 2016).

CAICW. The New ICWA Rules. Public Policy, Fargo: CAICW, 2016.

Cano, Regina Garcia. 2 Malnourished Girls Found on South Dakota Reservation. News, Seattle: Seattle Times, 2016.

CDC. “The Adverse Childhood Experience Study (ACE).” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Dept of Health and Human Services. 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/index.html (accessed 3 2018).

Center for Native American Youth. Fast Facts on Native American Youth and Indian Country. Statistical Facts, Washington DC: Aspen Institute, 2014.

Center for Native American Youth. Fast Facts on Native American Youth and Indian Country. Statistical Facts, Washington DC: Aspen Institute, 2011.

Cherokee Nation. Tribal Citizenship. 2019. https://www.cherokee.org/Services/Tribal-Citizenship (accessed 5 2, 2019).

Cherokee v. Georgia. 30 U.S. 1 (U.S. Supreme Court, 12 31, 1831).

Chief Joseph, of the Nez Perce. “The Surrender of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, Montana Territory.” Civil Rights and Conflict in the United States: Selected Speeches (Lit2Go Edition). October 5, 1877. http://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/185/civil-rights-and-conflict-in-the-united-states-selected-speeches/4856/the-surrender-of-chief-joseph-of-the-nez-perce-montana-territory-october-5-1877-chief-josephs-own-story/ (accessed November 7, 2018).

Chief Seattle. “Speech Cautioning Americans to Deal Justly with His People.” Civil Rights and Conflict in the United States: Selected Speeches. 1 12, 1854.

Child Welfare Information Gateway. “Determining the Best Interest of the Child.” Child Welfare Information Gateway. HHS/ ACYF/ACF Children’s Bureau. 2016. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/best_interest.pdf (accessed 3 11, 2017).

Churchill, Ward, interview by Joshua Frank. Accusations and Smear: An Interview with Professor Ward Churchill, (Part 1 of 5) (9 19, 2005).

Cleaveland, Bonnie PhD ABPP. Split Feather: An Untested Construct. Scientific Analysis, Charleston: Icwa.co, 2015.

Cohen, Felix S. “Colonialism: A Realistic Approach.” Ethics (The University of Chicago Press) 55, no. 3 (4 1945): 167-181.

—. Handbook of Federal Indian Law. 1942. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, [1942] 1971.

Cohen, Felix S. “Original Indian Title.” Edited by Lucy Kramer Cohen. Minn. L. Rev. (Yale U. Press) 32 (1947): 28.

Congress. “A Declaration by the Representatives of the United Colonies of North-America.” Journal of the Proceedings of the American Continental Congress, May 1775: 120.

Cross, Suzanne L, Angelique G Day, and Lisa G Byers. “American Indian Grand Families: A Qualitative Study Conducted with Grandmothers and Grandfathers Who Provide Sole Care for Their Grandchildren.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 25, no. 4 (12 2010): 371–383.

CTWS. “Declaration of Sovereignty.” Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Tribe of Oregon. 2016.

Declaration of Sovereignty(accessed 4 8, 2019).

Curry, Brett W. “Architect of Justice: Felix S. Cohen and the Founding of American Legal Pluralism, by Dalia Tsuk Mitchell.” Law and Politics Book Review, Sept 2007: 764-767.

Dawes Commission. Congressional Commission, Washington DC: Congress, 1895.

De Venter, M., K. Demyttenaere, and R. Bruffaerts. “The relationship between adverse childhood experiences and mental health in adulthood. A systematic literature review].” Tijdschr Psychiatry 55, no. 4 (2013): 259-68.

DHHS/IHS. Trends in Indian Health. Statistics, Washington DC: Indian Health Service, 1997.

DHS. ICWA from the Inside Out: ‘Split Feather Syndrome’. Article, Dept of Human Services, State of Minnesota, St. Paul: DHS, 2005.

DOI. Cohen’s Handbook of Federal Indian Law. Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1958.

DOI/BIA. “Guidelines for State Courts and Agencies in Indian Child Custody Proceedings.” Federal Register / Vol. 80, No. 37 /. 2 25, 2015. http://www.bia.gov/cs/groups/public/documents/text/idc1-029447.pdf (accessed March 15, 2015).

DOI-BIA. Indian Population and Labor Force Report. Statistics, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Department of Interior, Washigton DC: Department of Interior, 2003.

DOJ. “Environment and Natural Resources Division.” The United States Department of Justice. 5 24, 2015. https://www.justice.gov/enrd/timeline-event/congress-passes-first-indian-trade-and-intercourse-act (accessed 2 10, 2018).

—. “Indian Country Justice Statistics.” Office of Justice Programs: Bureau of Justice Statistics. 4 30, 2018. https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=tp&tid=200000 (accessed 8 19, 2018).

—. “Lead up to the Indian Claims Commission Act of 1946.” United States Deptartment of Justice. 5 12, 2015. https://www.justice.gov/enrd/lead-indian-claims-commission-act-1946 (accessed 6 1, 2019).

—. “Transcript from the First Hearing of the Advisory Committee of the Attorney General’s Task Force.” American Indian/Alaska Native Children Exposed to Violence. Bismarck: Department of Justice, 2013. 46.

Dudley, Richard G. Jr. MD. “Childhood Trauma and Its Effects: Implications for Police.” Edited by Harvard Kennedy School. New Perspectives in Policing Bulletin ( U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice), 2015: 1-22.

Duro v. Reina. 495 U.S. 676 (U.S., 1990).

Eaglewoman, Angelique, and G. William Rice. “American Indian Children and U.S. Indian Policy.” Tribal Law Journal 16 (2016): 1-29.

Enlow, Michelle Bosquet, Emily Blood, and Byron Egeland. “Sociodemographic risk, developmental competence, and PTSD symptoms in young children exposed to interpersonal trauma in early life.” Journal of Traumatic Stress (International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies), 2013: 686-694.

Executive Office of the President. Native Youth Report. Policy Brief, Washington DC: The White House, 2014.

FBI. “Indian Country Crime.” FBI.gov. 2016. https://www.fbi.gov/investigate/violent-crime/indian-country-crime (accessed July 27, 2016).

Feldon, Gai. Constitutional Government and Free Enterprise. Dubuque: Kendall Hunt Pub Co, 2014.

Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS. “Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study.” American Journal of Preventative Medicine (National Institutes of Health) 14, no. 4 (5 1998): 245-58.

Fiddler, Mark. “Adoptive Couple V. Baby Girl, State ICWA Laws, and Constitutional Avoidance.” Minnesota State Bar Association Family Law Forum (Minnesota State Bar) 22, no. 2 (Spring 2014): 10.

—. “Existing Indian Family Doctrine.” Letter to supporters. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Indian Child Welfare Law Center, 2 21, 2004.

Fineday, Anita. The ICWA Expert Witness and the Role of the Attorney for the Parent. Powerpoint, Casey Family Programs, Seattle: Casey Family Programs, 2012.

Flatten, Mark. Death on a Reservation. Phoenix: Goldwater Institute, 2015.

Fletcher, Matthew L.M. “Anishinaabe Law and the Round House.” Albany Government Law Review, 2017: 24.

Fletcher, Matthew L.M. “The Iron Cold of the Marshall Trilogy.” N.D. Law Rev (Michigan State University College of Law) 82 (2006): 627.

FOCSE. Tribal & State to Establish & Enforce Child Support. Publication, Washington DC: Federal Office of Child Support Enforcement , 2005.

Fort, Kate. Initial Observations on the ICWA Regulations. Blog, Indigenous Law and Policy Center, Michigan State University College of Law, Indigenous Law and Policy Center, 2016.

Fort, Kathryn E. 2018 ICWA by the Numbers. Statistics, Indigenous Law and Policy Center, Michigan State University College of Law, Turtle Talk, 2019.

Fort, Kathryn E. ICWA by the Numbers 2015. Statistics, Indigenous Law and Policy Center, Michigan State University College of Law, Turtle Talk, 2016.

Fort, Kathryn E. ICWA by the Numbers 2016. Statistics, Indigenous Law and Policy Center, Indigenous Law and Policy Center, Turtle Talk, 2017.

Fort, Kathryn E. ICWA by the Numbers 2017. Statistics, Indigenous Law and Policy Center, Michigan State University College of Law, Turtle Talk, 2018.

Franson, Janet, interview by Elizabeth Morris. Homicide Investigator (Ret), Founder, Lost and Missing in Indian Country (9 7, 2016).

GAO. Review of American Indian Policy Review Commission. Accounting and Financial Reporting, General Government Division, Congress, Washington DC: General Accounting Office, 1977, 14.

General Congress. “Declaration of Independence.” University of Oklahoma College of Law. July 4, 1776. http://www.law.ou.edu/ushistory/decind.shtml.

George, Robert P. “Natural Law, the Constitution, and the Theory and Practice of Judicial Review.” Fordham Law Review 69, no. 6 (2001): 2269.

Gerard, Forrest J. Assistant Secretary of Interior. Letter, Department of Interior, Washington DC: House of Representatives, 1978, 32.

Goldwater Institute. GOLDWATER INSTITUTE FILES CLASS ACTION LAWSUIT AGAINST PARTS OF INDIAN CHILD WELFARE ACT. July 7, 2015. http://goldwaterinstitute.org/en/work/topics/constitutional-rights/equal-protection/goldwater-institute-files-class-action-lawsuit-aga/ (accessed June 20, 2016).

Gould, L Scott. “The Congressional Response to Duro v. Reina: Compromising Sovereignty and the Constitution.” Edited by UC Davis Law School. U.C. Davis Law Review 28, no. 1 (1994): 53, 63 69-75.

GWIF. Foster Care Statistics 2016. U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children and Families; Children’s Bureau. 2018. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/foster.pdf#page=1&view=Introduction (accessed 3 29, 2019).

Haas, Theodore H. “Ten Years of Tribal Government Under I.R.A.” DOI.gov. United States Indian Service. 1947. https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/migrated/library/internet/subject/upload/Haas-TenYears.pdf (accessed 5 2, 2019).

Hagedorn, Nancy L. “”A Friend to go between Them”: The Interpreter as Cultural Broker during Anglo-Iroquois Councils, 1740-70.” Ethnohistory (Duke University Press) 35, no. 1 (1988): 60-80.

Hagen v. Utah. (US Supreme Court, 1994).

Hallie Bongar White, Jane Larrington. “INTERSECTION OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND CHILD VICTIMIZATION IN INDIAN COUNTRY.” Justice.gov. April 21, 2014. https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/defendingchildhood/legacy/2014/04/21/intersection-dv-cpsa.pdf (accessed July 28, 2016).

Harper, Fowler Vincent. “Natural Law in American Constitutional Theory.” Michigan Law Review 26, no. 62 (1927): 62-82.

Hart, H.L.A. “Positivism and the Separation of Law and Morals.” Harvard Law Review (The Harvard Law Review Association) 71, no. 4 (1958): 593-629.

Hazard, S., ed. Pennsylvania Archives (1st Series). Vol. 3. Philadelphia, PA: Joseph Severns, 1852.

Herman, Ellen. Adoption Statistics. Department of History, University of Oregon. 2 24, 2012. https://pages.uoregon.edu/adoption/topics/adoptionstatistics.htm (accessed 3 29, 2019).

Hintz, James R. “Wilson v. Marchington: The Erosion of TribalCourt Civil Jurisdiction in the Aftermath of Strate v.A-1 Contractors.” Public Land and Resources Law Review, 1999: 145.

Holder, Eric. “Attorney General Eric Holder Delivers Remarks During the White House Tribal Nations Conference.” Justice News. Washington DC, 12 3, 2014.

Horwitz, Sara. “The hard lives – and high suicide rate – of Native American children on reservations.” National Security. March 9, 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/the-hard-lives–and-high-suicide-rate–of-native-american-children/2014/03/09/6e0ad9b2-9f03-11e3-b8d8-94577ff66b28_story.html (accessed July 27, 2016).

Hyland, Duane. Running Head: Considering Indian Country. Topic Proposal, Rapid City: NFSH.org, 2014.

ICC. Indian Claims Commission Final Report. Final Commission Report, United States, Washington DC: GPO, 1978.

IHS. Indian Health Service. 2019. https://www.ihs.gov/aboutihs/ (accessed 3 28, 2019).

In re Alexandria Y. G018179 (Fourth Dist., Div. Three, 5 31, 1996).

In re Bridget R. B195282 (Cal. App. 4th, 41 Cal. App. 4th 1483 January 19, 1996).

In re Santos Y. B144822 (Cal. App, 4th, 92 Cal.App.4th 1274 2001).

In re Z.R. and L.R., adoptive parents v . 27-JV-FA-17-117 (MN Court of Appeals, 11 2017).

Indian Country Child Trauma Center. Demographics. Statistical Facts, Oklahoma City: Indian Country Child Trauma Center, 2005.

Indian Treaties Printed by Benjamin Franklin, 1736–1762. Philadelphia, PA: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1938.

Jackson, Andrew. “President Jackson’s Message to Congress “On Indian Removal” .” Records of the United States Senate, 1789 ‐ 1990 (National Archives and Records Administration (NARA]) Record Group 46 (Dec. 1830).

Jackson, Jack C. “Director of Government Affairs, National Congress of American Indians (NCAI).” National Conference of American Indians. February 12, 1999. http://www.ncai.org/ncai/resource/documents/governance/cvrightcensus.htm (accessed 2007).

James Bell Associates, Inc. “Analysis of Funding Resources and Strategies Among American Indian Tribes.” Administration of Children and Families. March 31, 2004. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/fund_res.pdf (accessed June 22, 2016).

Janney, Samuel M. The Life of William Penn. 2nd. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo, 1852.

Jefferson, Thomas. “To Major John Cartwrigt Monticello, June 5, 1824.” American History: From Revolution to Reconstruction and Beyond. Edited by University of Groningen. 1824. http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/presidents/thomas-jefferson/letters-of-thomas-jefferson/jefl278.php (accessed June 30, 2016).

Jerry Gardner, Executive Director Tribal. “Tribal Law & Policy Institute.” Santa Monica: ACF, 8 2, 2013.

Johnson v. M’Intosh. 21 U.S. 543; 1823 U.S. 293; 5 L. Ed. 681; 8 Wheat. 543 (U.S., 2 1823).

Jones, B.J. Overview of the Indian Child Welfare Act. 2006. http://www2.mnbar.org/sections/children/history.pdf (accessed April 29, 2007).

Jore, Rick, interview by Elizabeth Morris. Former Montana State Representative (11 15, 2016).

Kaplan, Sarah. “Native American couple sues to let their child be adopted by a white family.” Washington Post. June 10, 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2015/06/10/native-american-couple-sues-to-let-their-child-be-adopted-by-a-white-family/ (accessed June 21, 2016).

Karnowski, Steve. Feds Say Native Mob Gang Dented but Work Remains. Minneapolis: ABC News, 2013.

Katz, Colleen C, Mark E Courtney, and Elizabeth Novotny. “Pre-foster Care Maltreatment Class as a Predictor of Maltreatment in Foster Care.” Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 34, no. 1 (2 2017): 35-49.

Kelley, Marylouise (ACF). “Service needs in rural North Dakota and Montana.” Family Violence Prevention and Services Program Director. Washington DC: ACF, 9 23, 2013.

Kelly, John. “38 Years After ICWA, Feds to Collect Data on Native American Foster Youth.” The Chronicle of Social Change, April 8, 2016.

Kennerson, Marilyn (ACF). “Changes at ACF: Our own takes Casey position at ACF/BIA.” Washington DC: ACF, 8 5, 2013.

Kingfisher, Billie J. Jr. Dogma: Felix S. Cohen, The Indian Law Survey and the Spanish Model. Dissertation, Masters of Arts in History, Oklahoma State University, Graduate College, 2016.

Kinney, Adam F. “The Tribe, the Empire, and the Nation: Enforceability of Pre-Revolutionary Treaties with Native American Tribes.” Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law (Case Western Reserve University School of Law) 39, no. 3 (2007-2008): 897.

Krakoff, Sarah. “They Were Here First: American Indian Tribes, Race, and the Constitutional Minimum.” Stanford Law Review 69 (Feb 2017): 491-548.

Kunesh, Patrice H. A Call for an assessment of the Welfare of Indian Children in South Dakota. Article, Harvard Kennedy School (HKS); University of South Dakota, Harvard University, Vermillion: South Dakota Law Review, Vol. 52, No. 247, 2007.

LaBeau v. Dakota. 2:92-CV-203 (US Federal District Court: West. Dist. Mich., March 17, 1993).

Lawrence, William J. “In Defense of Indian Rights.” Beyond the Color Line; New Perspectives on Race and Ethnicity in America (Hoover Institution Press), 2002: 391-404.

Legal Inf Inst. Wex Legal Dictionary. Ithaca: Cornell Law School, 2019.

LexisNexis. Cohen’s Handbook of Federal Indian Law. LexisNexis, 2005.

Locust, Carol. Split Feather Study. Pilot Study, Native American Research and Training Center, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson: Pathways, 1998.

—. “Split Feathers Study.” American Indian Adoptees. n.d. https://blog.americanindianadoptees.com/p/split-feathers-study-by-carol-locust.html (accessed 2 5, 2018).

—. “Split Feathers: Adult American Indians Who Were Placed In Non-Indian Families As Children.” Native Canadian. n.d. http://nativecanadian.ca/Native_Reflections/split_feather_syndrome.htm (accessed 2 5, 2018).

Locust, Carol. Training Director. Pilot Study, Native American Research and Training Center , University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson: Pathways, 1998.

Lynch, Judy D. “Indian Sovereignty and Judicial Interpretations of the Indian Civil Rights Act.” Washington University Law Review 1979, no. 3,16 (1979): 897.

MacDonald, Peter. “White House Address on the Navajo Code Talkers.” American Rhetoric, Online Speech Bank. Washington DC, Nov. 27, 2017.

Malone, Tim. The Role of Indian Tribes in our Constitutional System – Two Persistent Problems. Conference, Olympia: Unpublished, 1988.

Margold, Nathan R. “Wheeler-Howard Act–Interpretation” Question 9.” Op. Sol. I.D. Ind. Aff 1917-1974 1 (1934): 484, 490-491.

Marston, Blythe W. “Alaska Native Sovereignty: The Limits of the Tribe-Indian Country Test.” Cornell International Law Journal 17, no. 2 (1984): 33.

Martin, Kenneth. “Thomas Sullivan.” Indian Affairs. Washington DC: Indian Affairs, 11 22, 2013.

Mcmullen, Marrianne (ACF). “Region 8 damaging tribal relations.” Spirit Lake. Washington DC: ACF, 11 1, 2013.

McMullen, Marrianne. “Decision on Proposed Removal.” Memorandum. Washington DC: ACF, 5 6, 2016.

McNeil, Kent. “Sovereignty and Indigenous Peoples in North America.” Articles and Book Chapters (Osgoode Hall Law School of York University) 22, no. 2 (2016): 25.

McWilliams, Paul. “English Common Law: Embodiment of the Natural Law.” The Western Australian Jurist 1 (2010): 128-131.

Means, Russell. “Statement to the Senate Special Committee on Indian Affairs.” American Rhetoric, Online Speech Bank. Washington DC, Jan. 30, 1989.

Meggitt, Jane. Government Money for Native Americans. Online, Bisfluent, Leaf Group Ltd, 2017.

Meyers, Peter C. “Frederick Douglass’s America: Race, Justice, and the Promise of the Founding.” First Principle Series, Jan 11, 2011, 35 ed.: 18.

Michael R. Tilus, PsyD, MP (HHS Public Health). “Letter of Grave Concern: Spirit Lake Tribal Social Services Grievances.” To Ms. Sue Settle, Chief, Dpt of Human Services, BIA. Devils Lake, North Dakota, March 3, 2012.

Miles v. Family Court for Jud’l Dist of Chinle. (Navajo Nation Supreme Court, Arizona January 2008).

Mission Indian Agency. “The Wheeler-Howard Bill – Questions and Answers.” Bulletin. Riverside, CA, April 16, 1934.

Mississippi Choctaw Indians v. Holyfield . 87-980 (U.S. Supreme Court, April 3, 1989).

Mitchell, Donald Craig. Wampum. New York: The Overlook Press, 2016.

MN Dept Human Serv. “Tribal/State Agreement.” St. Paul, Minnesota: State of Minnesota, Feb 22, 2007. 37.

Montana v. United States. (U.S. Supreme Court, 1981).

Moore, Johnston. “The Misapplication of The Indian Child Welfare Act.” The Chronicle of Social Change. April 1, 2015. https://chronicleofsocialchange.org/child-welfare-2/the-misapplication-of-the-indian-child-welfare-act/10872 (accessed June 21, 2016).

Morandi, Larry. “Tribal Trust Lands: From Litigation to Consultation.” States and Tribes: Building New Traditions, August 2004.

Morris v. Tanner. 160 Fed. Appx. 600 (9th Cir. 2005) (PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI, April 2006).

Morris, Elizabeth. Child Abuse within Indian Country. Literature Review, Helm’s School of Gov’t, Liberty University, Lynchburg: Unpublished, 2016.

Morris, Elizabeth. Spirit Lake Town Hall, February 27. Primary, witness, Fort Totten: CAICW, 2013.

Morris, Elizabeth. The Implications of Native American Heritage on U.S. Constitutional Protections. Lynchburg: Unpublished, 2017.

Morris, Roland John. Testimony before the Senate Select Committee on Indian Affairs. Seattle: Concerning Tribal Jurisdiction, 1998.

Morton v. Mancari. 417 U.S. 535 (U.S. Supreme Court, 6 17, 1974).

MSU. “The French and Indian War.” MSU College of Social Science. Edited by Randall Schaetzl. Dept of Geography, Environment and Spatial Science. 2018. http://www.geo.msu.edu/extra/geogmich/frenchindian_war.html.

NARA. “Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes (The Dawes Commission), 1893-1914.” National Archoves. June 26, 2017. https://www.archives.gov/research/native-americans/dawes (accessed 4 26, 2019).

—. “President Jackson’s Message to Congress “On Indian Removal”.” Records of the United States Senate, 1789 ‐ 1990;. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA]. Dec. 6, 1830. (accessed 2018).

Natelson, Rob. “Constitutional Law Professor.” Email Correspondence. 1 22, 2019.

Natelson, Robert G. “The Legal Meaning of “Commerce” in the Commerce Clause.” St. John’s Law Review 80 (2006): 789, 805–06.

Natelson, Robert. “The Original Understanding of the Indian Commerce Clause.” Denver University Law Review 85 (2007): 201.

NAU. “Indigenous Voices of the Colorado Plateau: The Merriam Report of 1928.” Northern Arizona University Library. Northern Arizona University. 2005. http://library.nau.edu/speccoll/exhibits/indigenous_voices/merriam_report.html (accessed 6 14, 2019).

NCAI. Trust Land. 2017. http://www.ncai.org/policy-issues/land-natural-resources/trust-land (accessed 11 17, 2017).

Newell, Terry. Statesmanship, Character, and Leadership in America. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2012, 2012.

Nicolai, Shanley Swanson, and Merete Saus. “Acknowledging the Past while Looking to the Future: Conceptualizing Indigenous Child Trauma.” Child Welfare Journal 92, no. 5 (2012): 110.

NICWA. Testimony of Sarah L. Kastelic. Testimony, Washington DC: Commission to Eliminate Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities, 2015, 1-17.

NICWA, SAMHSA. “Native Children: Trauma and Its Effects.” Trauma-Informed Care Fact Sheet. Portland: National Indian Child Welfare Association, April 2014.

NICWA/AAIA. A Guide to the Supreme Court Decision in Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl. White paper, Washington DC: Nat’l Indian Child Welfare Assoc. & Assoc on American Indian Affairs, 2013, 1-20.

NPS. “Pushmataha.” National Park Service. Sept. 14, 2017. https://www.nps.gov/people/pushmataha.htm.

O’Callaghan, E. B., ed. Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York. Albany, NY: Weed, Parsons, and Co.,, 1855.

Occom, Samson. “Short, Plain, and Honest Account of my Self.” Edited by Dietrich Reimer Verlag. Bernd Peyer, The Elders Wrote (Dartmouth College Archives), (1768) 1982: 12-18.

Osborn v. Bank of the United States. (United States Supreme Court, 1824).

Otis, D.S. The Dawes Act and the Allotment of Indian Lands. Edited by Francis Paul Prucha. University of Oklahoma Press , 1973.

Pommersheim, Frank. “Written testimony in support of the Indian Child Welfare Act to the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs.” (104th Cong. 1st Sess.) 1996: 432.

Poore, James A. “The Constitution of the United States Applies to Indian Tribes.” Montana Law Review 59, no. 1, Article 4 (Winter 1998): 51-80.

Poore, James A. “The Constitution of the United States Applies to Indian Tribes: A Reply to Professor Jensen.” Montana Law Review, 1995/1999: 19.

Prucha, Frances Paul. American Indian Policy in Crisis: Christian Reformers and the Indian, 1865-1900. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976.

Prygoski, Philip J. “From Marshall to Marshall: The Supreme Court’s changing stance on tribal sovereignty.” GP Solo Magazine, 7 2, 2015.

Publius. “Federalist Papers.” Yale Law School: Lillian Goldman School of Law. 1787. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed01.asp.

Pushmataha. “Response to Chief Tecumseh on War Against the Americans.” American Rhetoric, Online Speech Bank. Mississippi, 1811.

Raab. “Andrew Jackson.” Raab Collection. 10 15, 2019. https://www.raabcollection.com/andrew-jackson-autograph/andrew-jackson-signed-sold-president-andrew-jackson-original-instructions (accessed 3 10, 2019).

Reagan, Ronald. “Statement on Indian Policy, 1983.” The American Presidency Project. Edited by John Woolley, & Gerhard Peters. Univ. of Calif, Santa Barbara. 1 24, 1983. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=41665 (accessed 6 30, 2017).

Regan, Shawn. “5 Ways The Government Keeps Native Americans In Poverty.” Forbes. 3 14, 2014. http://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2014/03/13/5-ways-the-government-keeps-native-americans-in-poverty/#739501c6cc62 (accessed 12 16, 2016).

Reid v. Covert. 701 (US Supreme Court, 1956).

Reply Brief for the United States. 03-107 (U.S. Supreme Court, Washington DC 2003).

Rice v. Cayetano. 528 U.S. 495 (U.S., 2000).

Robinson Jr, John. “The Binding Guidance Principle: Using the Indian Trust Doctrine to Trump the APA.” American Indian Law Journal 4:1 (2015): 26.

Roe Bubar, Marc Winokur, Winona Bartlemay. Perceptions of Methamphetamine Use in Three Western Tribal Communities: Implications for Child Abuse in Indian Country. Investigative Report, West Hollywood: Tribal Law and Policy Institute, 2007.

Rollings, Willard Hughes. “Citizenship and Suffrage: The Native American Struggle For Civil Rights in the American West, 1830-1965.” Nevada Law Journal 5, no. 126 (Fall 2004): 126-140.

Rolnick, Addie. “The Promise of Mancari: Indian Political Rights as Racial Remedy.” NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW (University of Nevada, Las Vegas) 86 (2011): 102-183.

Roozen, Sylvia, Gjalt-Jorn Y. Peters, Gerjo Kok, David Townend, Jan Nijhuis, and Leopold Curfs. “Worldwide Prevalence of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Literature Review Including Meta-Analysis.” Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 40, no. 1 (1 2016): 18–32.

Roser, Max. Child Mortality. Statistics, Our World in Data, 2019.

Rowley, Sean. 43rd Symposium on the American Indian at Northeastern State University . April 17, 2015. http://m.tahlequahdailypress.com/news/icwa-discussed-at-symposium-seminar/article_08846b3a-e543-11e4-8421-7744ec7971c6.html?mode=jqm (accessed April 20, 2015).

Ruoff, A LaVonne Brown, ed. “Samson Occom (Mohegan) (1723-1792).” n.d.

Russell Means: About. 2014. http://www.russellmeansfreedom.com/about/ (accessed October 5, 2014).

Sampson, Dimitra H. Child and Sexual Abuse in Indian Country. Lecture, Sioux Falls: Dept. of Justice, 2007.

Scheel, Ann Birmingham. Arizona Indian Country Report. Annual Report, Phoenix: U.S. Dept. of Justice, 2011.

Schumacher-Matos, Edward. SD: Indian Foster Care 1: NPR Investigative Storytelling Gone Awry. Ombudsman Report, Ombudsman, National Public Radio, New York: National Public Radio, 2013, 80.

Scofield, Ruth Packwood. Behind the Buckskin Curtain. New York: Carlton Press, Inc., 1992.

Seattle, Chief. “Speech Cautioning Americans to Deal Justly with His People.” Civil Rights and Conflict in the United States: Selected Speeches (Lit2Go Edition). January 12, 1854. http://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/185/civil-rights-and-conflict-in-the-united-states-selected-speeches/4706/speech-cautioning-americans-to-deal-justly-with-his-people-january-12-1854/ (accessed November 7, 2018).

Skillen v. Menz. 1998 MT 43 (Supreme Court of the State of Montana, March 3, 1998).

Spaith, James. The Native American: At What Level Sovereignty? Draft, Exhibit 1, The White House, U.S. Government, Washington DC: Leonard Garment, Assistant to the President, 1974, 77.

Speed, Nathan. “Examining the Interstate Commerce Clause Through the Lens of the Indian Commerce Clause.” Boston University Law Review, 2007, 87 ed.: 467, 470-71.

Stephens v. Cherokee Nation. 423 (U.S. Supreme Court, May 15, 1899).

Strauss, Leo, and Joseph Cropsey. History of Political Philosophy. 3. Chicago: University of Chicago, 1987.

Stuart, Paul. Nations Within a Nation: Historical Statistics of American Indians. New York: Greenwood Press, 1987.

Sullivan, Thomas F. 12th Mandated Report. Denver: ACF, 2013.

Sullivan, Thomas F. 13th Mandate Report. Denver: ACF, 2013.

—. “Continual Rape of 13-yr-old Ignored.” To Superiors at the Administration of Children and Families. Denver, Colorado: ACF, June 10, 2014.

—. “Criminal Corruption continues at Spirit Lake.” To DC Superiors with the Administration of Children & Families. Denver, Colorado: ACF, May 6, 2014.

—. “Prevented from Testifying.” To Ms. McMullen. Denver: ACF, 7 1, 2014.

—. “Response.” To Ms. McMullen. Denver: ACF, 2 11, 2014.

—. “Sullivan rebukes his DC Superiors for their negligence of children on Indian reservations.” To ACF Superiors in DC. Denver: ACF, April 4, 2014.

—. “Summary of Correspondence.” Denver: ACF, 12 19, 2013.

Talton v. Mayes. 163 U.S. 376, 384 (U.S., 1896).

Texas Dept of Family and Protective Services. Legal Basis for Child Protective Services. Houston, n.d.

The Institute for Government Research. “The Problem of Indian Administration.” Edited by Lewis Meriam. Studies in Administration (The John Hopkins Press), February 1928.

The Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia. “To George Washington from James Bowdoin, 30 July 1776.” Founders Online, National Archives. 13 June, 2018. http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0378. (accessed July 30, 2018).

Turanovic, Jillian J, and Travis C Pratt. “Consequences of Violent Victimization for Native American Youth in Early Adulthood.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 46, no. 6 (6 2017): 1333 – 1350.

Udall, Representative Morris K. “The American Indians and Civil Rights.” Selected Speeches. Washington DC: Arizona University, 10 4, 1965.

United States. “Agreement with the Sisseton and Wahpeton Bands of Sioux Indians, Appendix.” First People. September 20, 1872. https://www.firstpeople.us/FP-Html-Treaties/AgreementWithTheSissetonAndWahpetonBandsOfSiouxIndians1872.html (accessed 5 2, 2019).

United States Commission on Civil Rights. “Enforcement of the Indian Civil Rights Act: U.S. Civil Rights Commission Hearing, Phoenix, AZ.” Washington DC: GPO, September 29, 1988.

United States. “Constitution.” Cornell University Law School: Legal Information Institute. 1787. https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/.

—. “General Allotment Act of 1887.” 24 Stat 388. Washinhgton DC, December 6, 1886.

—. “Indian Child Welfare Act OF 1978.” Vols. Public Law 95-608, 25 USC Chapter 2. Washington DC, 1978.

—. “Indian Civil Rights Act.” Vols. Public Law 90–284, 82 Stat. 73. Washington DC, 1968.

—. “P.L. 68-175: Indian Citizenship Act.” 43 Stat. 253, Ch. 233. Washington DC: GPO, June 2, 1924.

—. “The Dawes Act of 1887.” The Avalon Project – Yale Law School. 2008. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/dawes.asp (accessed 4 6, 2019).

—. “Transcript of Treaty of Fort Laramie.” OurDocuments.gov. April 29, 1868. https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=42&page=transcript (accessed May 2, 2019).

—. “Treaty with the Cherokee 7 Stat., 311.” Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Vol. II. Compiled by Charles J. Kappler. Washington, 5 6, 1828. 288-292.

—. “Treaty with the Chippewa.” 2 22, 1855.

—. “Treaty with the Omaha.” Treaties. March 16, 1854. http://resources.utulsa.edu/law/classes/rice/Treaties/10_Stat_1043_Omaha.htm (accessed May 2, 2019).

—. “Treaty with the Sioux – Sisseton and Wahpeton Bands.” First People. February 19, 1867. https://www.firstpeople.us/FP-Html-Treaties/TreatyWithTheSiouxSissetonAndWahpetonBands1867.html (accessed 5 2, 2019).

United States v. Billy Jo Lara. 541 U.S. (U.S. Supreme, 2003).

United States v. Lopez. 93-1260 (U.S.S.C., 4 26, 1995).

United States v. Rogers. 45 U.S. (4 How.) 567 (U.S. Supreme, March 9, 1846).

United States v. Wheeler,. 76-1629 (US Supreme Court, March 27, 1978).

Univ of Illinois. “Full text of “Monthly catalog of United States Government publications”.” LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSTIY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN. July 1947. http://www.archive.org/stream/monthlycatalogof531947unit2/monthlycatalogof531947unit2_djvu.txt (accessed 11 16, 2016).

Univ. Alaska. Indian Country Statute (1948). 2018. http://tribalmgmt.uaf.edu/tm112/Unit-2/Indian-Country-Statute-1948.

University of Oklahoma. Childhood Trauma Series in Indian Country. Presentation, Health Sciences Center, University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City: Indian Health Service TeleBehavior Health Center, 2013.

US Census Bureau. Nonwhite Population by Race. Statistics, Bureau of the Census, Dept of Commerce, Washington DC: Legislative Reference Service, 1960.

US Census Bureau. The American Indian and Alaska Native Population 2010. Statistics, Bureau of the Census, US. Dept of Commerce, Washington DC: US. Dept of Commerce, 2010.

US Census Bureau. Tribal Complete Count Committee Handbook. Bureau of the Census, Department of Commerce, Washington, DC: United States Census 2000, 2001, 4-99.

US Census Bureau. US Census. Statistics, US Census Bureau, Dept of Commerce, Washington DC: Dept of Commerce, 2000.

US Congress. “Congressional Record ICWA.” 95th Cong. 2nd Sess. 124 (1978): 38101-112.

US Congress, House. Concurrent Resolutions, Indian Affairs. House of Respresentatives, Washington DC: GPO, 1953.

—. “Oversight Hearing before the Committee on Resources, US House of Representatives, Subcommittee on Indian Affairs.” Child Protection and the Justice System on the Spirit Lake Indian Reservation. Washington DC: GPO: 113 Cong. 2nd Sess, June 24, 2014.

US Congress. Conference. S. 2981: An Act to authorize appropriations for the Indian Claims Commission for fiscal year 1977, and for other purposes. House Report: Rpt No. 94-1695, Interior and Insular Affairs, Congress, Washington DC: GPO: 94th Cong. 2nd Sess., 1976, 4.

US Congress. House. “H.R. 12533 – Indian Child Welfare Act.” Congress.gov. Washington DC: GPO: 95th Cong. 1st Sess., Nov. 8, 1978.

US Congress. House. H.R. 3286: Adoption Promotion and Stability Act of 1996. House Report: H. Rept 104-542, Committee on Ways and Means, House, Washington DC: GPO: 104th Cong. 2nd Sess., 1996.

US Congress. House. H.R. 3828: Indian Child Welfare Act Amendments of 1996. Congressional Report, Natural Resource Committee: Indian Affairs, House, Washington DC: GPO: 104 Cong. 2nd Sess., 1996.

US Congress. Senate. H.R. 3286: Adoption Promotion and Stability Act of 1996. Senate Report, Committee on Indian Affairs, Congress, Washington DC: GPO: 104TH Cong. 2nd Sess., 1996.

—. “Hearing Before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate.” Amendments to the Indian Child Welfare Act: S. Hrg. 104-574. Washington DC: GPO: 104th Cong. 2nd Sess, June 26, 1996.

—. “Hearing Before the Select Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate.” Indian Child Welfare Act: S. Hrg. 100-845. Washington DC: GPO: 100th Cong. 2nd Sess., May 11, 1988.

—. “Hearings before a Subcommittee of The Committee on Indian Affairs United States Senate.” Survey of the Conditions of the Indians of the United States. Washington DC: GPO: 70th Cong. 2nd Sess., 1929.

—. “Hearings before the Subcommittee on Indian Affairs of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs of the United States Senate.” Indian Child Welfare Program. Washington DC: GPO: 93rd Cong. 2nd Sess., April 7.8, 1974.

US Congress. Senate. Indian Child Welfare Act Amendment S. 569. Senate Bill, Indian Affairs Committee, Senate, Washington DC: 105th Cong. 1st Sess., 1997.

—. “Joint Hearing Before the Committee on Indian Affairs, US Senate and the Committe on Resources, US House of Representatives.” Indian Child Welfare Act: S. Hrg. 105-224. Washington DC: GPO: 105th Cong. 1st Sess., June 18, 1997.

—. “Oversight Hearing Before the Select Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate.” Indian Child Welfare Act: S. Hrg. 100-574. Washington DC: GPO: 100th Cong. 1st Sess., Nov 10, 1987.

US Congress. Senate. S. 1214: Indian Child Welfare Act. Congressional Report, Select Committee on Indian Affairs, Senate, Washington DC: GPO: 95th Cong. 1st Sess., 1977.

US Congress. Senate. S. 1962: Indian Child Welfare Act Amendment. Congressional Report, Committee on Indian Affairs, Senate, Washington DC: GPO: 104th Cong. 2nd Sess., 1996.

US Congress. Senate. S. 721 – An Act to authorize appropriations for the Indian Claims Commission for fiscal year 1974, and for other purposes. Senate Report: S.Rept 93-53, Interior and Insular Affairs, Congress, Washington DC: GPO: 93rd Cong. 1st Sess., 1973.

US Congress: House. “Hearings before the Subcommittee on Indian Aflairs and Public Lands of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs.” Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978. S.1214, Serial No. 96-42. Washington DC: GPO: 95th Cong; 2nd Sess., Feb-Mar 9, 1978. 308.

Vattel, Monsieur Emer (Emmerich) de. The Principles of the Law of Nature Applied to the Conduct and Affairs of Nations and Sovereigns. 6th American. Translated by Esq. Joseph Chitty. West Brookfield, MA: Merriam and Cooke, [1758,1773] 1844.

Vaughan, David J. Give Me Liberty: The Uncompromising Statesmanship of Patrick Henry. Edited by George Grant. Nashville: Cumberland House Publishing Inc., 1997.

Victoria, Franciscus De. The First Relectio Of The Reverend Father, Brother Franciscus De Victoria, On The Indians Lately Discovered. 1696. Edited by Johann Georg Simon. Translated by John Pawley Bate. Vol. 1. 2 vols. Ingolstadt, Cologne and Frankfort, 1580.

Vieru, Simona. “Aristotle’s Influence on the Natural Law Theory of St. Thomas Aquinas.” The Western Australian Jurist (Murdoch University) 1 (2010): 115-122.

Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. “The Treaty of Logg’s Town, 1752.” 1906: 154–174.

Wald, Patricia M. Assistant Attorney General. Letter, Department of Justice, Washington DC: House of Representatives, 1978, 35, 40.

Washington, George. “The Avalon Project: Washington’s Farewell Address.” Lillian Goldman Law Library. Yale Law School. 1796. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/washing.asp (accessed September 17, 2015).

Weingast, Barry R. “The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development.” The Journal of Law, Economics and Organization, 1995: 1-31.

White House. “Documents related to the Indian Claims Commission.” Documents 1973-77, Bradley H. Patterson Files, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, Washington DC, 1973-77, 18.

Wilkinson, Charles. American Indians, Time, and the Law: Native Societies in a Modern Constitutional Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1967.

Wilkinson, Charles F., and John M. Volkman. “Judicial Review of Indian Treaty Abrogation: As Long as Water Flows, or Grass Grows upon the Earth–How Long a Time is That.” California Law Review 63 (5 1975): 601-661.

Wilson, James. “Of the Natural Rights of Individuals.” Founding.com: A Project of the Claremont Institute. 1790-91. http://founding.com/founders-library/american-political-figures/james-wilson/of-the-natural-rights-of-individuals/ (accessed 4 8, 2019).

Woodward, Stephanie. “Suicide is epidemic for American Indian youth: What more can be done?” 100 Reporters. Oct 10, 2012. http://investigations.nbcnews.com/_news/2012/10/10/14340090-suicide-is-epidemic-for-american-indian-youth-what-more-can-be-done (accessed July 27, 2016).

Worcester v. Georgia. (US Supreme Court, 1832).